Recipe: Simmered Shiitake Mushrooms

Shiitake mushrooms are native to Asia but have become popular all over the world because they are versatile and packed with flavour. They are particularly popular in Japanese cuisine and have a variety of uses. They apparently have some medicinal properties but, more importantly, they are absolutely delicious. We have a fantastic recipe for simmered shiitake mushrooms which can be used as a side dish for many Japanese meals.

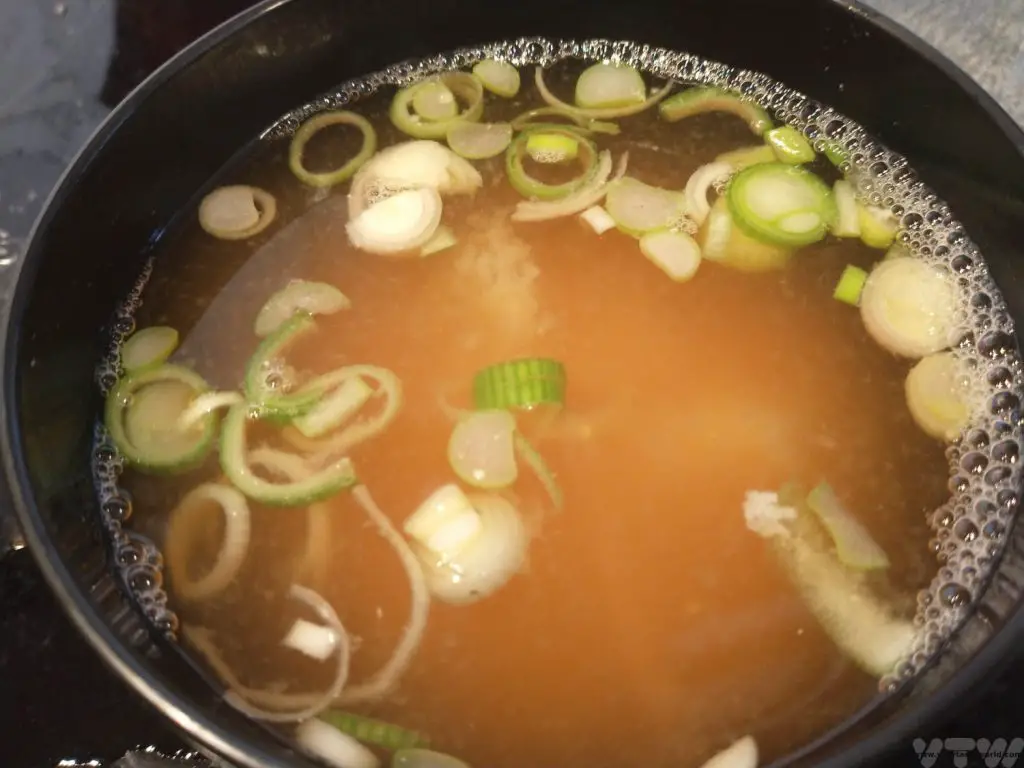

Shiitake can be used as a key ingredient for dashi – Japanese stock – which is used in many traditional dishes, including miso soup. Dashi often uses shaved bonito (a type of fish) flakes but this can be substituted for shiitake mushrooms, complemented with kombu seaweed, to make a flavoursome vegetarian/vegan dashi.

This recipe for simmered shiitake mushrooms is used as a side dish to accompany a wide variety of foods. It is packed with umami flavour which complements the sweetness of the mirin and the saltiness of the soy sauce.

This simmered shiitake dish is very simple to make but requires a little – minimal – preparation as you will need to presoak the mushrooms. Ideally, we recommend soaking the mushrooms overnight as this will allow maximum umami. If you can’t soak overnight, we suggest a minimum of five hours. Also, make sure that you save the water the mushrooms have been soaked in as that is packed with flavour.

How To Make Simmered Shiitake Mushrooms

Ingredients

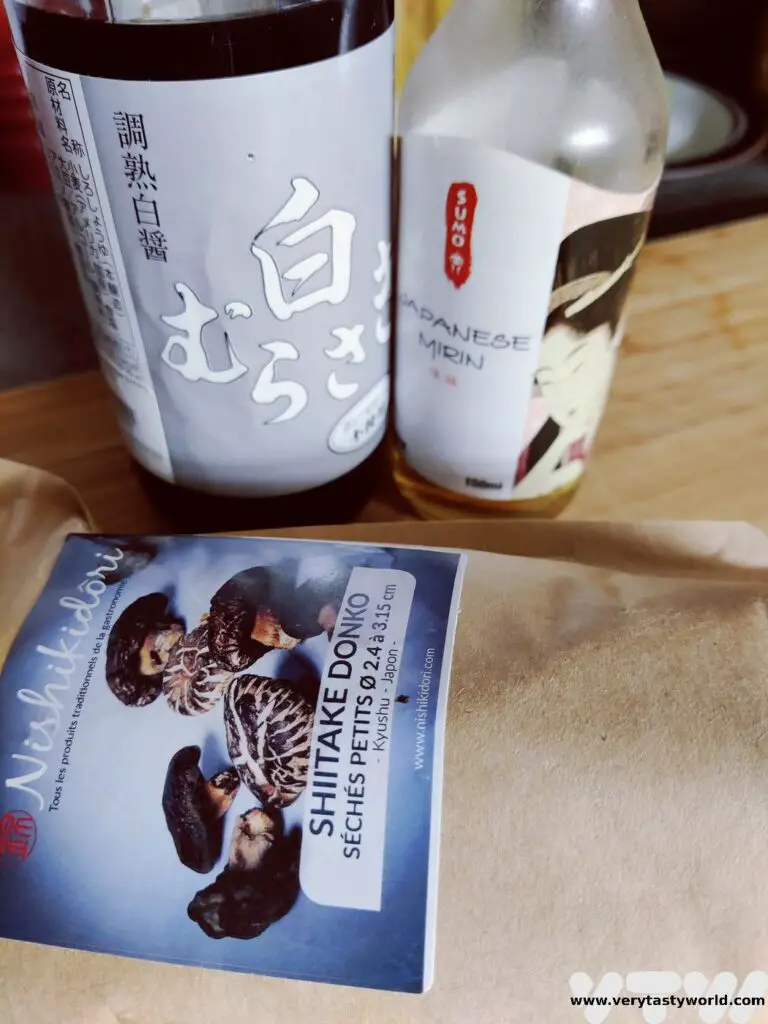

100g grams dried whole shiitake mushrooms

1 tbs soy sauce

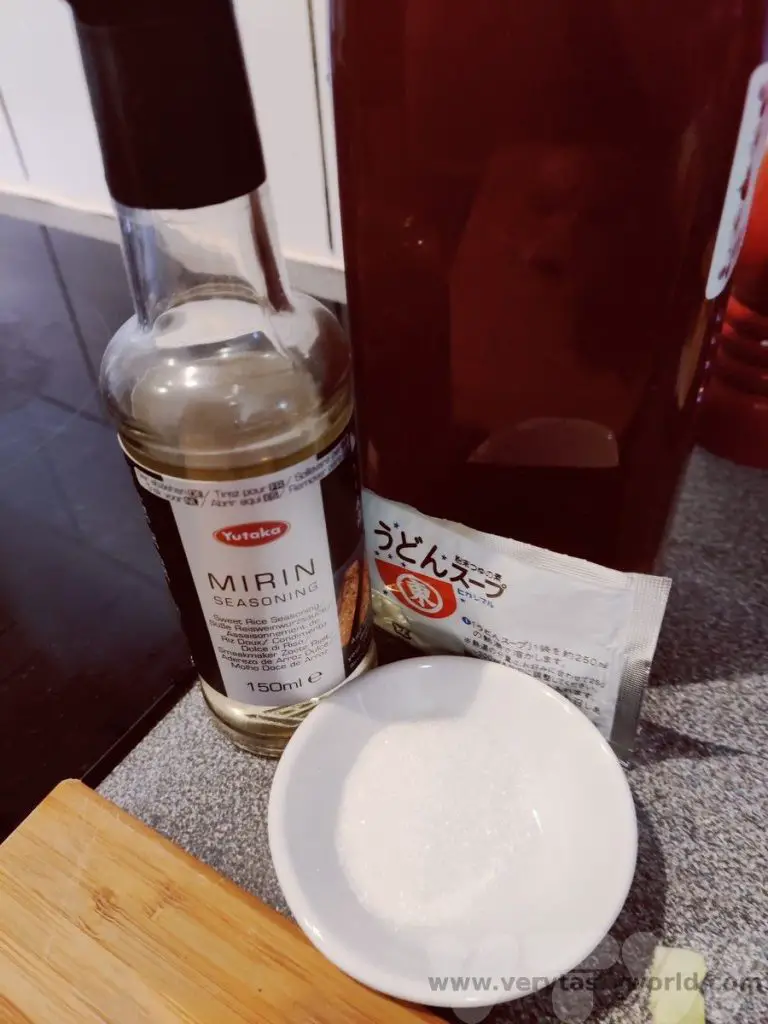

1 tbs mirin (if you can’t get mirin you can use 1 tbs cooking sake and 1 tsp sugar and if you can’t get cooking sake use 1 tbs white wine and 1 tsp sugar)

Water to cover the mushrooms

Method

Place the dried mushrooms into a bowl and cover – just to the top of the mushrooms – with water. Soak the dried mushrooms until they are soft. Ideally a minimum of 5 hours, overnight is better. Save the water!

Remove the mushrooms from the water. They should have turned from woody to plump and juicy. Take off the stems if you wish and cut into slices.

Put the mushrooms into a pan.

Add 1 tbs mirin and 1 tbs soy sauce.

Then add the mushroom water to just about cover them. Be careful as there may be a little bit of residue at the bottom of the water bowl, don’t let that go in.

Bring the mushrooms to a simmer until the water has evaporated. This will take about 15 mins.

Allow to cool and serve cold.

We often use these as a side to accompany a number of dishes – great eaten in the summertime with cold somen noodles, agedashi tofu (fried tofu), vinegared wakame (seaweed) and cucumber salad, and shira ae (mashed tofu and carrot salad).

Related Posts You May Enjoy

- RECIPE Oyakodon Donburi

- Zero Waste Recipes Before Your Holiday

- RECIPE: Vegetable Biryani Tamil Nadu Style

- RECIPE: Vegan Wild Garlic Pesto

- Recipe: Venetian Pasta Sauce

- RECIPE: Biryani Raita Recipe

- RECIPE: How to Make Costa Rica’s Gallo Pinto

- Recipe: Japanese Simmered Pork Belly – Buta no Kakuni

- RECIPE: How to Make Umeboshi

- Recipe: Simmered Shiitake Mushrooms

- How to Use Public Transport in Japan

- RECIPE Oyakodon Donburi

- Planning a Trip to Japan

- The Makanai: Cooking for the Maiko House

- Setsubun Food – Bean Throwing Day

- The Gassho Farmhouses of Rural Japan

- Recipe: Japanese Simmered Pork Belly – Buta no Kakuni

- RECIPE: How to Make Umeboshi

How to Use Public Transport in Japan

Japan is the most brilliant country to travel through – with exciting, vibrant, neon cities contrasting with serene temples, castle and pagodas alongside some stunningly beautiful countryside, it really has something to offer everyone. You can read about some of the finest places to visit in our guide to Planning a Trip to Japan. The best way to see all these amazing sights is to use public transport. The Japanese transportation network is fast and efficient throughout the whole country. It is also really well interconnected and integrated. Here are some tips for how to use public transport in Japan and the various transport options you might choose to use.

Please note that this post contains affiliate links. If you click through and decide to make a purchase we will make a small commission, at no extra cost to you, which will help towards the costs of running this site.

Travelling By Rail

Japan is famous for its rail network. It’s a great way to travel and is highly efficient. When planning your rail journeys we recommend the excellent Hyperdia site which has timetables and can offer information about all available routes.

If you are planning to travel through the country, it is worth considering a Japan Rail (JR) Pass. They are only available to visitors and, even though they aren’t cheap and the prices have recently increased significantly, they can represent good value. The rail pass would cover the cost of long trips between multiple cities. Beware though, if you are only staying in one city or even hopping between two (e.g. Tokyo to Kyoto and back) it’s not worth buying a rail pass. There is a JR calculator which can help you decide whether it is worth investing in a pass.

It is worth having a think about your trip when planning: If you want to spend a few days in Tokyo before travelling around the country, don’t activate your card until you need to travel outside the city. You might be able to buy a shorter duration card and hence pay less money. Alternatively you might want to consider inter-city buses which are slower but cheaper.

It is possible to buy 7, 14 or 21 day cards, either standard fare or Green Class (first class but, honestly, standard class is fantastic) and you can use them on most bullet trains as well. You need to order your pass before you travel.

You will get a voucher which you then exchange for a rail pass at a JR station. Not all stations issue passes but the main stations and stations at airports will have them. The clock starts ticking from the time you activate your card.

When using the JR pass, just have it ready at the entrance/exits to the platforms at the stations. You can’t go through the automatic gates but there will always be a station attendant on duty in an office at one end of the barriers. Show the card – with the date facing towards them – and they will wave you through.

In terms of knowing when you are arriving at your destination, most platform signs will have the name of the station in roman characters but they will be smaller than the main sign in Japanese. Keep an eye out for them – you’ll soon get used to spotting them. Also, many trains will announce the next station, so you can listen out. The announcement will be along the lines of, “Tsugi wa Destination desu.”

Beware: Not all rail lines are JR. There are quite a lot of private lines running throughout the country, including in some of the cities, so you will have to buy a separate ticket. The delineation between the lines should be clear – if you are changing trains from JR to the private line you will exit the JR station (showing your pass) and can then use a machine to buy a ticket for the line you wish to use.

Fun fact: One of the delightful things about the Tokyo JR lines (and in other cities) is that each station has its own jingle – a short tune that plays when you arrive at the station. You can even buy CDs of all the tunes!

Using the Shinkansen – the Bullet Train

There’s a reason the shinkansen is known as the ‘bullet train.’ If you visit Japan do try to ride the bullet train at least once, it’s part of the experience. You can use your JR pass on all bullet trains, except the super-fast Nozomi. (Don’t worry, the other bullet trains are still very fast indeed.) Most electronic signs toggle between Japanese and English these days so have a look at the boards and wait a few moment to check which platform your train will depart from.

If you are using the shinkansen and have a JR Pass, you can reserve seats for free. Just pop along to a JR booking office – most stations will have them, and the station doesn’t need to be a shinkansen station – and book the seats. You will need to make sure you know which train you want to travel on. We often use Hyperdia to give us a timetable that shows us a variety of options and, as our plans for the day develop, we can point to the particular train we would like to travel on.

We do recommend making a reservation early if you know your plans. Sometimes trains can book up a few days beforehand, so you would have to rely on unreserved seating.

Your ticket will show the car and seat number. On arrival at the platform the car numbers are clearly marked. The platform will indicate where the train will stop for your particular car. Stand in the queue at your boarding point. Everybody is very polite and organised and it’s an efficient way of boarding the train.

Unreserved seating is available on most bullet trains but, as you would expect, you are not guaranteed a seat. We recommend showing up at the platform well before the train arrives and get a good place in the queue. The unreserved cars will be marked so follow the signage to that part of the platform.

Travelling on the shinkansen is a real pleasure. The seats are comfortable and have loads of legroom.

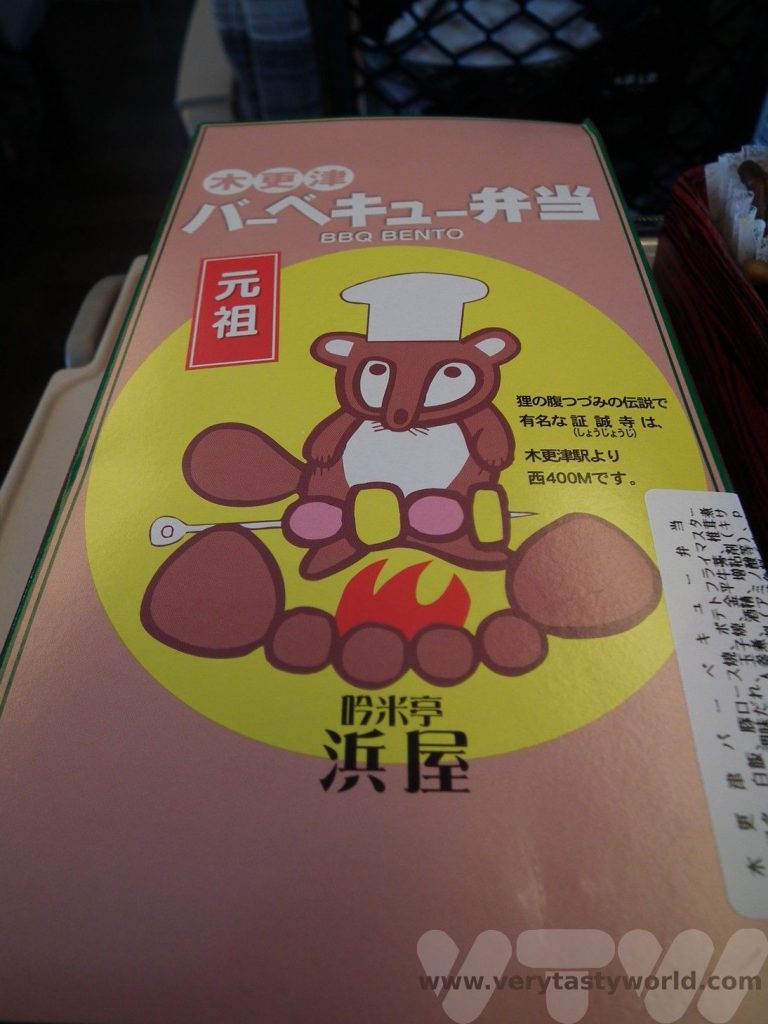

Foodie Tip: Don’t forget to get a bento box for your journey. It’s an essential part of the travelling experience. These are lunch boxes which contain all sorts of lovely delicacies. Many stations will offer ekiben (station bento) as local specialities.

You can buy food (and drinks, including alcohol) on the train itself. A delightfully low-key attendant glides up and down the carriage, gently asking if you would like to buy anything. But it is more expensive to buy food on the train so we often stock up at the station or a convenience store before we board. It’s absolutely fine to bring your own food.

There will usually be a vending machine or three on the platform – vending machines can be found everywhere in Japan. You can even get a can of hot coffee from some machines!

How To Use the Metro/Subway

Many of Japan’s larger cities also have a metro system. You cannot use your JR pass here. You can pay for each journey but some metro lines have an all-day ticket pass, so it’s worth investigating those, depending on how much you plan to use the transport during the time period you are travelling.

Timing Tip: Metro stations can get extremely busy at rush hour. If you are planning to travel inter-city we recommend waiting until after 9am on weekdays before setting off. If you do need to leave early you may well see immaculately clad, gloved attendants on the platform ensuring that everyone can squish aboard the train.

We recommend buying an e-money card – Suica or Passmo are popular choices. You can charge your card and simply tap in and out of metro stations, the cost being automatically deducted at the gate machine. These cards can also be used in places like konbini – convenience stores – such as Lawson, Family Mart or 7-Eleven. They are often specific to the city/region so can’t necessarily be used all across Japan. For example, a Tokyo card is unlikely to work in the Kansai region.

Charging the cards is easy – most convenience stores will have the ability to do this. You can say, “kono kādo ni chāji shite kudasai,” and indicate the amount. Note that you will need cash to top up these cards, you cannot charge from a bank card or credit card.

If paying for individual tickets, there will be plenty of ticket machines at the metro station. The metro map may seem intimidating if you can’t read Japanese but there is usually an English map – although you might have to look for it. We’ve often downloaded subway maps in English onto our mobile phones. The prices are based on distance, so you need to check what your fare would be using the map.

There is usually a screen which allows you to select a language and buy tickets in English.

The Japanese language machines may seem a bit daunting but are usually quite visual. You can often select the number of tickets by pressing the button showing the number of people (adults and/or children) travelling. These are the characters to look out for:

Adult (big person): 大人

Child (small person): 小人

If you get really stuck, we’ve often found local people hovering close to the machines, keeping an eye on us to see if we need help. If you say “Destination ni ikimasu” – I’m going to Destination – in all likelihood someone will help you. Don’t forget to thank them – “arigato.”

And if the worst comes to the worst, if you get the cost wrong, the barrier will close on you when you put your ticket in the exit machine and you can just pay the difference at the other end – there will be a member of staff in a booth who can take the excess fare.

When entering and exiting the platform either tap your card or put your individual ticket into the barrier machine. The barriers generally remain open but close rapidly if there is a problem. Be warned: don’t trip over them!

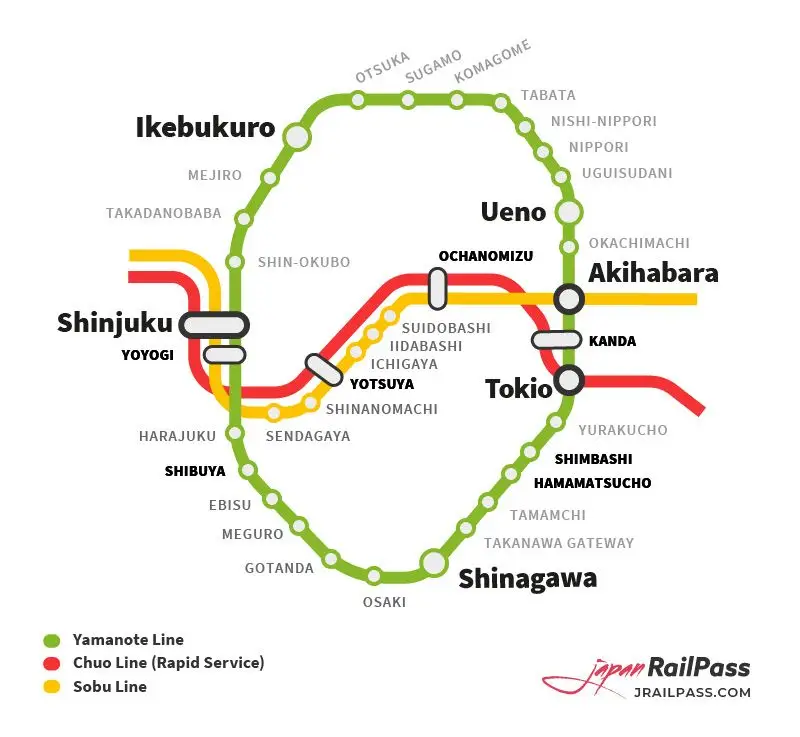

Tip: In Tokyo the Chuo (Rapid) Line and the Yamanoto Line are both Japan Rail so if you have activated your JR Pass you can use it on these tracks. The Yamanoto is a circular route and the Chuo goes straight through the centre of the city so you can reach plenty of stations. Both stop at Tokyo (labelled Tokio here) station where you can connect with the shinkansen.

Travelling on Buses in Japan

Japan has a good bus network which is useful if you are planning to explore some of the more rural areas. There are also bus connections in cities. There will usually be a bus stop close to the railway stations and often they are waiting, ready for the arrival of the train.

Buses can be a bit more challenging than trains as it’s sometimes difficult to know when you have arrived at your stop (although we have often asked the driver the name of the location we are planning to arrive at and they will indicate that you’re on the right bus).

You can ask, “Destination ni ikimasu ka”- does it go to Destination? The driver will indicate whether they do. If a driver crosses their arms in front of them in an X-shape, that’s an indication that the bus doesn’t go to that particular place.

Ticketing and payment systems can vary between companies. Some will have a fixed fare where you get on at the front door and pay the driver.

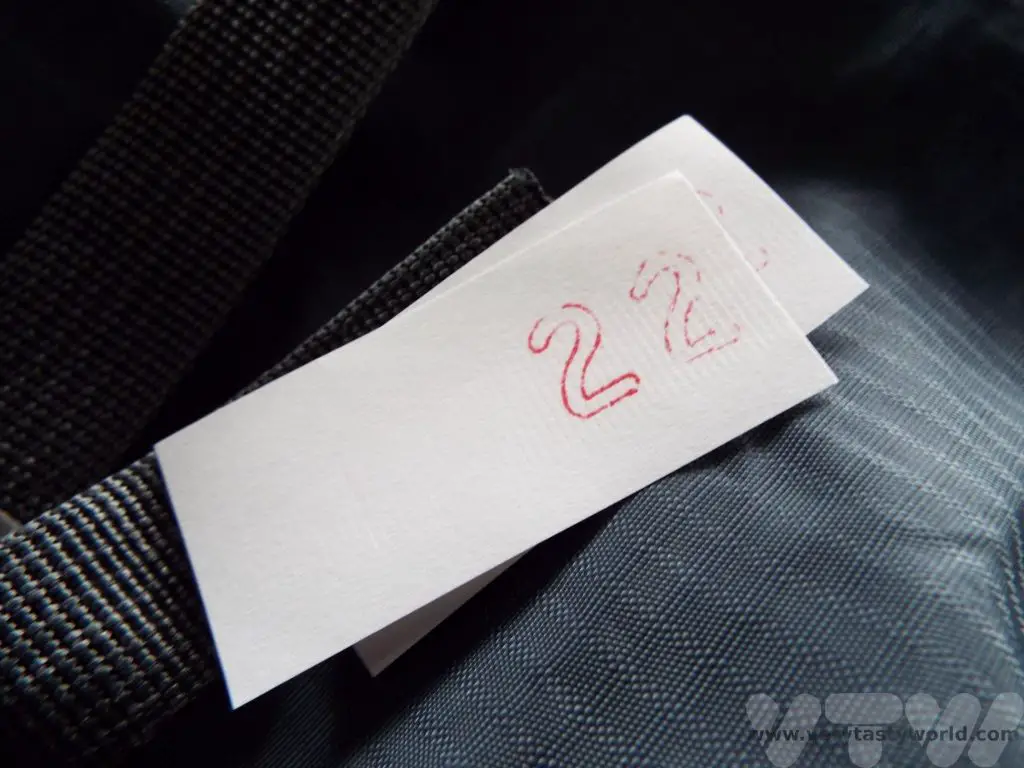

Others have boarding towards the middle or rear of the bus. When getting on, grab a ticket. It will have a number on it.

At the front of the bus you will see a display with grid of numbers showing costs in yen that increase as the journey progresses.

When you want to get off, press the bell, then make your way to the front of the bus. The cost on the grid corresponding to the number on your ticket is the price and you pay the driver by putting money into the slot on your way out.

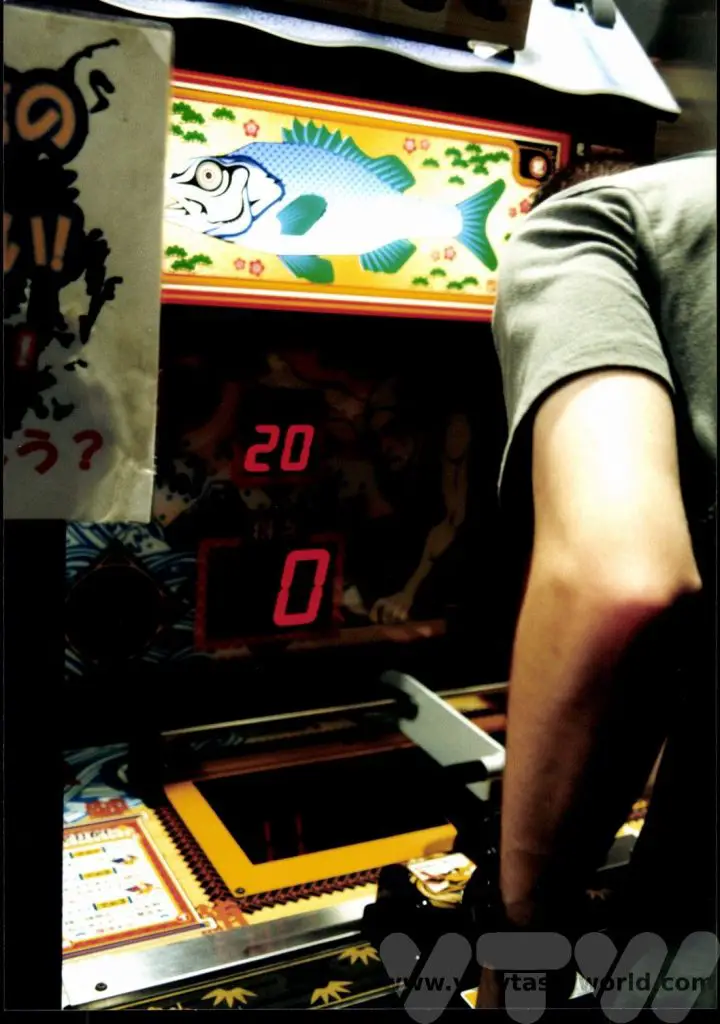

Some buses offer change, others don’t, so always try to keep a few 100 Yen coins in change. (And if you don’t spend the 100 Yen coins on the bus, you can easily spend the money playing video games in the multitude of city arcades – so much fun!)

If we’re unsure, we just copy the other passengers!

Ferries in Japan

Japan has a lot of islands along its coastline and there are multiple ferries that you can use to reach them. Ferries are generally easy to use. We have pre-booked some in the past, especially when we visited places that were part of our itinerary and we had already booked hotels. But if we are visiting a particular attraction, we just use ferries on the day.

Japanese Taxis

Taxis in Japan are pretty expensive, so we tend to avoid using them. They are usually clearly marked with a taxi light on the roof. Inside the windscreen there will be neon sign; a red light usually means available and a green light means the taxi is already occupied. You can hail a cab just as you would in many parts of the world. Drivers are reliable and courteous but usually don’t speak much English so it’s a good idea to have your destination written down in Japanese. Hotels/accommodation may have business cards, so you might be able to pick one up in the lobby – you can show it to your driver.

If you do hop into a cab, the driver will open the door for you from the driver’s seat, it’s automatic. Payment is usually cash but some drivers might take credit cards. Most rides are metered but for some you may be able to agree a fixed fare based on a fixed journey – e.g. to an airport.

Hire car in Japan

If you are travelling in more remote parts of Japan a hire car may be a good option to explore the area. The Japanese Alps are great for driving through. We hired a car on the tiny island of Yakushima and found it was perfect for giving us flexibility. Driving is on the left, as it is in the UK.

Air

It is possible to fly between locations but we wouldn’t recommend it. Even a long journey on the shinkansen would get you to your destination within a comparable time, especially after all the faff getting to an airport and going through security etc.

Most airports are located a fair way from the cities they serve – e.g. it is around a 1.5 hour journey from Shinjuku, Tokyo to Narita Airport. Most airports will have trains shuttling between the airport and the city. Some also have what are called limousine buses, coaches that will travel to particular destinations from the airport to the city.

Trams

Some cities have tram systems. We’ve used trams in Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Hakodate and Kagoshima. They work in a similar way to buses except it’s often a bit easier to know when you have reached your destination because they are on rails and the tram stops often have a sign! They are usually fixed-fare and you pay at the end of the trip.

Some trams have machines will only take the correct amount of coins but a lot of the tram stops/stations will have a money changing machine where you can exchange notes for coins. Again, all-day passes are usually available and can be purchased ahead of time, often at stations or tourist offices. Some tram systems will also allow you to tap your e-money card if you have one for the area.

Transportation for your Luggage

Another tip for travelling in Japan is to use the amazing takkyuubin is a luggage forwarding service that will get your bags from one end of the country to the other overnight. It’s reasonably priced and highly efficient. Although there are many companies, the most well known is Yamato Transport Co , characterised by its kuroneko – black cat – logo with a black cat carrying a black kitten.

We have used this service many times and it has always been exceptionally good. Every business hotel or ryokan we have stayed at has been entirely helpful in arranging the transportation. Say, “Takkyuubin dekimasu ka?” and the helpful staff will not only have the forms, they will fill them out for the luggage destination in Japanese for you. (You can say, “Nihongo o kakemasen” – I can’t write Japanese – if you have the hotel information in kanji).

The staff will often telephone the destination hotel to check that it’s okay for them to receive your luggage and they will hold luggage for a few days if needed. You need to do a little preparation – it’s advisable to send bags the evening before you travel at the latest. And we always make sure we have our next hotel’s name written in Japanese so that the staff can know exactly how to complete the form. (Accommodation sites such as booking.com offer the booking in local language as well as your native language.)

We’ve often sent our luggage to the hotel ahead of time, swanned onto the shinkansen carrying only a day pack, and arrived at our destination to find that our bags have already been sent up to our room.

Quirky Travelling in Japan

Ropeways and Funiculars

Japan is a very mountainous country and many cities have viewing points from the tops of hills and mountains. There are often ropeways and funiculars to take you up to the top so that you can enjoy the spectacular views.

Fun Fact: Did you know that Japan has three officially designated “top views”?

Pirate Ships!

The Fuji Five Lakes area is a lovely place to visit and reasonably easy to reach from Tokyo, even as a long day trip. There are loads of things to do – we particularly enjoyed taking the funicular over the smoking volcano where you can visit a splendid sculpture park. And you can take trips across the lake on a… pirate ship! If you’re super-lucky, you might even catch a glimpse of the illustrious Mount Fuji, Japan’s national mountain. We were unlucky, unfortunately the area is often cloudy.

Other Travelling in Japan Tips

It’s worth noting that Japan is still a largely cash-based society. Cash machines are being used more but you can’t always rely on them being available, especially if you are travelling outside the big cities. That said, Japan is also a very safe society and, although nothing is 100% safe, we’ve never felt uncomfortable carrying cash.

Some Useful Words and Phrases

| Does this go to [destination] | [Destination] ni ikimasu ka |

| Where is the train station? | Eki wa doko desu ka |

| Where is the bus stop | Buseto wa doko desu ka |

| Where is… | … doko desu ka |

| How much is this? | kore wa ikura desu ka |

| Asking someone to point to a location on a map (where is here?) | koko wa doko desu ka |

| Can I make a reservation | yoyaku ga dekismasu ka |

| I have a reservation | yoyaku ga arimasu |

| Train/bullet train/bus/car | densha/shinkansen/basu/kuruma |

| Please/thank you/excuse me | onegaishimasu/arigato/sumimasen |

Related Posts You May Enjoy

- Recipe: Simmered Shiitake Mushrooms

- How to Use Public Transport in Japan

- RECIPE Oyakodon Donburi

- Planning a Trip to Japan

- The Makanai: Cooking for the Maiko House

- Setsubun Food – Bean Throwing Day

- The Gassho Farmhouses of Rural Japan

- Recipe: Japanese Simmered Pork Belly – Buta no Kakuni

- RECIPE: How to Make Umeboshi

RECIPE Oyakodon Donburi

Oyakodon is a hug in a bowl – the ultimate in Japanese comfort food. Donburi are rice bowls topped with meat, fish, vegetables and other delicious ingredients. Oyakodon is a special type of donburi, which means ‘mother and child’. This is because the main components are chicken and egg! It’s an easy dish to make at home, so here is our recipe for oyakodon.

The great thing about oyakodon is that it is a simmered dish – no frying is needed. It’s also a one pot dish, where (apart from the rice) everything is cooked in the same pan. It has a lovely complex flavour – umami from the dashi (stock), salty from the soy sauce and sweet as well, a great combination.

There are specialist oyakodon restaurants in Japan – the dish is cheap and popular and, of course, delicious.

The base of okyakodon is dashi, a Japanese stock usually made from kombu (kelp seaweed), bonito flakes (shaved fish flakes) or shiitake mushrooms. The ingredients are simmered in water for several minutes and then removed leaving a clear stock full of umami flavour. Dashi forms the basis of many Japanese soups including its famous miso soup.

We have a recipe for dashi here. But if you don’t have time (or ingredients) to make dashi you can buy dashi powder online or at Asian supermarkets. It is possible to make oyakodon without dashi and still get bags of flavour. If you can’t find the powder or don’t want to use dashi, chicken stock or a stock cube will add excellent flavour.

We always use chicken thigh meat to make oyakodon as it has loads more flavour than chicken breast. Interestingly, while chicken breast meat is more expensive than thigh meat in the UK, it’s the other way round in Japan. Chicken thighs are considered to be the best meat for this dish. However, if you prefer chicken breast it’s absolutely fine to use that instead – the flavour of the broth is fantastic and because you are simmering the meat, it won’t go dry but will remain tender and juicy.

Oyakodon Equipment and Pans

If you go to an oyakodon restaurant in Japan they have special pots to cook the food in for individual portions which means that you get the omelette perfectly balanced atop the chicken.

But if you’re cooking at home for more than one person, and are serving different portions from the same pot it’s a bit more difficult to get the fluffy omelette on top. But however you present the food, it is still guaranteed to taste delicious! We tend to use as small a saucepan as we can get the ingredients into – that is with the smallest diameter – in order to get the egg to rest on top.

We have a rice cooker which is absolutely brilliant for cooking rice. Add rice and water (twice as much as the rice by volume), pop on the lid, press the switch and it will cook the rice perfectly, automatically switching itself to a keep warm function. If you don’t have a rice cooker you can cook the rice in a saucepan – same ratio, just let the rice simmer until all the water has absorbed.

Recipe Oyakodon: Ingredients

2 chicken thighs per person

1 onion

100ml dashi (if you can’t get dashi use chicken stock)

1 tbs soy sauce

1 tbs mirin (If you can’t get mirin, use cooking sake. If you can’t get cooking sake use white wine. Whatever substitute you use, add an extra teaspoon of sugar.)

1 tsp sugar

2 eggs

Rice – about 100g per person

2 spring onions (green onions) to serve

Method

Start cooking your rice. We use sushi rice as it has a nice texture. We put it in a rice cooker but you can use a pan on the stove. The ratio for both methods to use is 1 cup of rice to 2 cups of water. Cook until all the water is absorbed.

Chop up the chicken into bite-sized pieces. Slice the onion into thin slices.

Make the dashi or stock and add the soy sauce, mirin and sugar. Put into the smallest diameter pan you have (it needs to be deep enough to accommodate all the ingredients). Bring to a boil. When the liquid is simmering add the raw chicken. Stir it around to make sure each piece can cook.

Allow the chicken to simmer for about 5 minutes.

Add the onion on top and simmer further for about 10 minutes.

Let everything simmer until the rice is cooked.

Beat the eggs gently in a bowl.

At last minute pour the egg slowly on top of the chicken and onions. Turn the heat off and let the eggs cook for a couple of minutes in the residual heat.

Place the rice in a bowl.

Then slide the chicken, egg and any broth on top. This is the tricky part. You can buy special donburi pans which can cook an individual portion that glides neatly onto the rice bowl. But in a practical kitchen, when you are cooking one dish for more than one person and using a standard saucepan, it’s a bit trickier to produce multiple portions without the egg breaking up. So, you may not be able to get the perfect presentation but the finished result will still taste utterly delicious.

Finely chop the spring (green) onions and use them for garnish. Enjoy!

Related Posts You May Enjoy

- RECIPE Oyakodon Donburi

- Zero Waste Recipes Before Your Holiday

- RECIPE: Vegetable Biryani Tamil Nadu Style

- RECIPE: Vegan Wild Garlic Pesto

- Recipe: Venetian Pasta Sauce

- RECIPE: Biryani Raita Recipe

- RECIPE: How to Make Costa Rica’s Gallo Pinto

- Recipe: Japanese Simmered Pork Belly – Buta no Kakuni

- RECIPE: How to Make Umeboshi

- Recipe: Simmered Shiitake Mushrooms

- How to Use Public Transport in Japan

- RECIPE Oyakodon Donburi

- Planning a Trip to Japan

- The Makanai: Cooking for the Maiko House

- Setsubun Food – Bean Throwing Day

- The Gassho Farmhouses of Rural Japan

- Recipe: Japanese Simmered Pork Belly – Buta no Kakuni

- RECIPE: How to Make Umeboshi

Planning a Trip to Japan

Regular readers of this blog will know that we are absolutely in love with Japan. The land of the rising sun is beguiling, fascinating and loads of fun. It is a country where bright, vibrant, blaring neon cities contrast with the elegance of traditional castles, temples, pagodas and exquisite gardens. We first visited Japan over twenty years ago and have returned many, many times. Here’s our guide to planning a trip to Japan.

Getting There

Most people will fly into Japan either to Tokyo or Kansai (Osaka). Both airports are located a fair distance from the cities they serve but it’s easy to pick up public transport options to reach the metropolis. There are train services that run regularly and also limousine buses, which can get you to the city centres very easily.

Getting Around

Japan’s public transportation system is fully integrated and highly efficient. If you are travelling for any length of time and especially travelling between cities, we recommend the Japan Rail Pass.(It’s not recommended if you are only staying in one city as it wouldn’t be cost-effective.) The JR Pass is valid on all Japan Rail services, including the shinkansen bullet train, with the exception of the super-fast Nozomi service. Don’t worry, the other bullet trains are still pretty damned fast! And they are the most amazing way to travel.

You can buy a pass that is valid for 7, 14, or 21 days. Also, the JR Pass allows you to book seats on the shinkansen for free. Just book your seats at any JR office at any station.

You need to order the pass before you travel. You will receive a voucher. This is then exchanged at a JR station for your pass. It is time-stamped and valid from the first day of use on the stamp. There is a ticket office at Narita airport where you can get your pass – just follow the signs for the trains. Be aware that there may be a queue as lots of other tourists will be wanting to do the same as soon as they get off the plane. If you don’t want to activate it straight away, that’s fine.

When using the pass you don’t need to go through the usual entry/exit barriers. Just show your pass to the station staff in the office located at one side of the barriers and they will wave you through.

If travelling by train you can plan your journey using the excellent hyperdia website. Note that there are some private railways in Japan, notably in more rural areas, and the JR Pass is not valid on these.

Bus services in Japan are reliable and reasonably comfortable. They are especially useful when travelling through the countryside.

Taxis are available in most cities but they are expensive. They all have automatic doors.

Car hire is also easy to arrange if you want to visit rural areas. There is really no need to hire a car if you are visiting cities.

Accommodation

There are a variety of options depending on your budget. You can book standard hotels via the usual booking sites.

We tend to stay in business hotels, especially in the cities, as they offer cheap accommodation, albeit in tiny rooms. You can see our post about business hotels. They are very small but they contain all the facilities you might need. And you’re in Japan – you don’t want to spend all your time in a hotel room!

However, it is also worth splurging for a night or two to stay in a ryokan – a traditional Japanese inn. These often comprise several rooms, all laid out with tatami (reed) mat flooring. Your bedding will be a futon laid out on the floor.

You may well be served your dinner in your room. At other establishments you will eat dinner in the restaurant and your futon will be laid out by the maid while you are dining.

Ryokan may be ensuite although sometimes these establishments will have shared facilities. Some have lovely baths and you may be offered a time slot for bathing.

Money

Japan is still a largely cash-based society and, although ATMs have become more common over the years, are still not as widespread as you might think. We tend to take Japanese yen with us. And, while no destination is 100% safe, we have always felt comfortable carrying cash and have never had any problems while doing so.

Most hotels and increasing numbers of shops and restaurants accept credit cards these days.

You can also get IC cards – Passmo and Suica are popular ones in Tokyo – that you can all over the metropolitan area you are visiting. You can tap them to use public transport, such as the metro, and use them to buy some products as well. It is possible to charge them up by adding more cash at convenience stores (known as konbini), such as Family Mart, Lawson and 7-11, which can be found all over Japan.

Just be careful that they are valid within the area you are travelling. For example a card used in Tokyo and the surrounding area may not be accepted in the Kansai region.

Eating and Drinking

Dining when you can’t understand the writing on the menu can be a bit daunting. When we first visited Japan English menus didn’t exist but these days increasing numbers of restaurants offer menus in English, Chinese and Korean.

And many restaurants have picture menus or plastic models of the food in the window. They will also show the prices, sometimes in ordinary numerals but sometimes in Kanji (the Japanese writing system). If you get really stuck, take your server outside and point at what you want!

Food is eaten with chopsticks and occasionally a spoon. It is rare to find knives and forks, and restaurants are usually unable to supply them. Bring your own if needed, but, better, learn to use chopsticks – it isn’t that difficult!

Most people will know the Japanese foods sushi, sashimi and ramen noodles but the cuisine has so much for offer.

There are prices to suit all budgets, from noodles at a railway station stand, where you eat standing up, to the full-on kaiseki ryori, Japanese haute cuisine.

And, if you are travelling on the train, it’s essential to enjoy a bento box meal – a lunch box full of goodies. There are even regional variations of bento sold at railway stations, known as eki-ben.

Izakaya are Japanese style pubs where you can enjoy drinks as well as order a variety of dishes.They are a great way to spend an evening.

Beware the cover charge, known as otoshi or tsukidashi, which is basically a table charge. Some establishments will have a fixed charge for drinking and eating there. It’s usually a few hundred yen per person and its aim is to encourage you to stay at that establishment. If you get a small starter or plate of snacks just after you sit at your table, it’s not a freebie, you are likely to be charged for it. Some bars in Tokyo will indicate whether a cover charge applies but it’s not always clear.

Tipping is not expected nor required in Japanese restaurants or bars – which makes life very easy. Just pay the bill. We have had some instances where restaurant proprietors have run after us with 5 yen change!

Customs and Etiquette

When we first visited Japan we were worried that we would fail to follow etiquette and make terrible faux pas all the way around the country. In fact Japanese people are incredibly friendly and welcoming and would not ostracise a visitor. But if you get the etiquette correct, your efforts are really appreciated.

As with travelling anywhere, it goes without saying that you should be polite and respectful. ‘Arigato’ means ‘thank you’ and ‘sumimasen’ means ‘excuse me’.

Absolute no-nos are wearing outdoor shoes inside. Always remove them before entering a home. Some restaurants may also request shoe removal and provide a locker for your shoes and some slippers that you can wear inside.

If you are using a shared bathroom at your accommodation bear in mind that your room slippers need to be changed for bathroom slippers. (Don’t forget to change them back when leaving the bathroom!)

If using a shared bath, for example at an onsen (hot spring resort), you should wash before getting into the bath so that you are clean before you start bathing. The bath is all about having a lovely, relaxing soak at the end of a day’s sightseeing.

If you are wearing a yukata (a cotton kimono) make sure that the left side of the material overlaps the right side- right over left is for dressing the dead.

Tattoos are still taboo in Japan because they are associated with yakuza (gangsters). If you plan to spend time in an onsen it is worth covering small tattoos with a sticking plaster. Be aware of tattoo polices, some accept people with tattoos, others may turn you away.

As mentioned above, you don’t tip in Japan. Unless you are staying at a high-end ryokan, where it is polite to leave a few hundred yen for the maid who will have laid out your bedding, although this isn’t compulsory. It is considered rude to hand people cash, so leave any tip in an envelope.

Handy Travelling Tips

If you are travelling on public transport and have a lot of luggage, it’s not the most comfortable way to travel, especially if you are lugging unwieldy cases. Instead you could use the Takkyubin service – a courier delivery service that will transfer your luggage to your next location (or beyond, hotels are usually happy to store your bags for a few days). Just ask for ‘Takkyubin’ at a hotel. The staff will be able to arrange it for you and take payment on your behalf. It’s a pretty cheap service and is extremely efficient. Our bags have travelled from one end of the country to the other overnight and we’ve just swanned up at the hotel with a daysack the following day and our luggage arrived ahear of us.

Useful hint: it’s helpful to have the address of your destination hotel written in Japanese – hotel staff will be happy to fill in the form for you. If you are using a booking service such as Booking.com, you can obtain a printout or use the app to find the address in the original language.

Another thing that you will notice about Japan is the sheer number of vending machines. It feels as though there is one on every corner. You can buy pretty much anything. Most are snacks and drinks machines, some will be able to sell hot beverages as well, and you can even buy beer. (We couldn’t imagine a full and working vending machine selling beer in the UK – it would get trashed in seconds!)

And you can drink the tap water in Japan, so make sure to bring a reusable water bottle with you.

Planning A Trip To Japan -Things to Do

Of course Japan offers all the usual attractions for tourists, such as museums, galleries, entertainment and shopping opportunities galore. But here are some quintessentially Japanese activities.

Kabuki

Kabuki is a form of Japanese highly stylised drama and it’s possible to visit the theatre in Ginza, Tokyo to see a play. When we visited we were given a leaflet which explained the plot for the play we were watching. The word kabuki is a combination of three characters which mean song (ka), dance (bu) and acting (ki) so you can expect all of these elements. All performers are male, even those playing female roles.

Another thing that surprised us is that there is an element of audience participation where viewers shout words of encouragement to their favourite actors. You can get tickets for a single act or a whole play.

Arcades

If you’re a big kid and enjoy playing video games you’ll love the arcades in Japan. They can be found in any city. We can’t resist them – you can play all sorts of games from musical (drumming or dancing) to driving to betting on horse races. There are some where you can stand alongside a mannequin comedian and attempt to perform as a manzai (straight man, funny man comedy).

Just make sure you have a stash of 100 Yen coins.

Karaoke

Karaoke was invented in Japan and is now popular all over the world. The word derives from ‘kara’, meaning empty and ‘oke’ which is an abbreviation of ōkesutora (orchestra). In Japan you can visit karaoke establishments and hire a room for a set time period – just for you and your mates or travelling companions – thumb through the extensive book of songs (there will be loads in English) and sing your socks off. It’s great fun and there’s no need to worry about singing in front of strangers.

Big Echo is one of the most famous karaoke venues. You can also get a nomihodai – all you can drink – deal. There’s a phone where you can order drinks – although it would be helpful to be able to speak a bit of Japanese. The phone will also ring to let you know when you have 10 minutes before the room hire expires – the perfect time make Bohemian Rhapsody your final number!

Manga, Anime and Electronics

Japanese culture, particularly manga and anime, has become hugely popular all over the world and there are lots of opportunities to visit museums, such as the wonderful Studio Ghibli museum, and even museums located by some of the animation studios. There are some areas within certain cities which have hubs where you can go shopping for all the latest hi-tech gear or discover pop culture galore. Akihabara in Tokyo and DenDen town in Osaka offer loads of exciting places to explore for tech and culture fans alike.

Sumo

Sumo is Japan’s national sport and is fascinating to watch. There are tournaments six times a year (three in Tokyo, alternating with ones in Osaka, Nagoya and Fukuoka) You can spend a day at the sumo if your trip coincides with a basho.

The rules of sumo are very simple: Two wrestlers face each other in a ring and, at the signal of mutual consent to begin, the bout commences. A wrestler loses when he is either forced out of the ring or touches the floor with any part of his body other than his feet.

You can read about our day at the sumo in this post. And if you can’t attend, you can often watch sumo wrestlers training at their stables.

Pachinko

Pachinko is definitely the loudest and possibly the most impenetrable activity we have ever done in Japan. It’s kind of like a vertical pinball machine where you pay for a bucket of silver balls, put them in the machine and turn the nob. Sometimes you might win a whole bunch of silver balls. You exchange these for a prize (which can be a bit bizarre, such as a box of razor blades!) which can then be swapped for cash in the booth outside the pachinko parlour.

This is gambling, which isn’t strictly legal in Japan, which is why you win a ‘prize’ rather than directly winning cash. The most we have ever spent is 1000 Yen (a few pounds) and, of course, we lost. We didn’t have a clue what we were doing but it was lots of fun anyway. Although our ears were ringing after leaving the room.

Onsen

Because Japan is located in the Pacific Ring of Fire it is geothermally very active and has a lot of hot springs. And a country that has a lot of hot springs has a lot of hot spring resorts. Onsen are delightful places to relax and unwind, soaking in natural spring water. Some ryokan have their own onsen. A rotemburo is an outdoor onsen where you can relax and enjoy the natural surroundings. It’s worth knowing that some onsen are sex-segregated. We like bathing together, so tend to seek out private baths where we can relax together. Some of the ryokan we have stayed have a rotemburo which can be booked for a set time each evening.

The bath etiquette is that you undress in the changing area then have a shower/wash before you get into the bath. Make sure you have thoroughly rinsed off all soapy water. This means that you are clean before bathing and can just enjoy a lovely relaxing time in the warm water.

Castles

There are thousands of castles all over Japan. These impressive fortresses, constructed from stone and wood, were often strategically located along trade routes and were designed to provide strong defences. Many become the residences of feudal lords, known as daimyo,

Many Japanese castles are reconstructions, having been destroyed by fire and rebuilt over the centuries.

Some of the best castles are to be found at Matsumoto – the black crow castle…

…and Himeji.

Gardens

Japanese gardens feature traditional designs that have their roots, if you will, in the country’s indigenous Shinto religion which recognises gods and spirits that are found in all things. Gardens often reflect the nature of the landscape and Japan’s distinctive seasons and use natural materials such as rocks, stones and water. Some gardens are very specialist, such as the zen gardens which comprise a minimalist landscape of rocks and stones.

Planning a Trip To Japan – Top Places to Visit

Here are a few suggestions for places to visit which will hopefully give you a flavour of what Japan has to offer as well whet your appetite for some local regional dishes.

Honshu – the main island

Tokyo

Japan’s capital city is a sprawling metropolis. There are so many places to explore and things to do you could spend your entire holiday here. Popular districts are Shinjuku, Shibuya (the place where young people hang out), Asakusa (a laid-back area with old-world feel which is home to the Senso-ji temple), Akihabara (the cool hi-tech area which has a lot of manga and anime stores as well as the Tokyo Anime Center) and Roppongi (the area where a lot of overseas residents and visitors reside or hang out).

We tend to stay in Shinjuku as it’s very central. There are all sorts of things to do, including foodie tours.

The Meiji shrine, dedicated to the deity of the Emperor Meiji is set in a lovely extensive park. It has a dramatic torii gate at its entrance.

Shibuya is the location of the famous road crossing – known as ‘The Scramble’ – and seen in many films and TV series where over 2000 people can cross in a single cycle of the pedestrian lights.

If you like the animations of Studio Ghibli, The Ghibli Museum in Mitaka is a must-see but you do have to book in advance.

Odaiba is an entertainment hub on an artificial island set in Tokyo Bay. Cross the rainbow bridge to find all sorts of activities and shopping. And a monument that somehow seems familiar…

There are also plenty of day trips from Tokyo. Nikko is a historic city and the home of the Toshogu Shinto shrine.

A tour of the Fuji Five Lakes area is a possibility from Tokyo. You might get a glimpse of Japan’s iconic mountain (if the weather is clear!) and sail on a pirate ship across Lake Ashinoko.

Osaka

A few hours from Tokyo on the bullet train Kansai’s commercial capital is a neon paradise and a fantastic place for foodies. Head out to the dotonbori area for a range of amazing restaurants and a vibrant nightlife.

Typical Osaka dishes include okonomiyaki (kind of a cross between an pancake and a pizza) and takoyaki – octopus balls in batter.

Nara

A tour of this ancient city offers lots of historic buildings, temples and pagodas to explore all set within a park. The highlight is Tōdai-ji which houses Daibutsu, a 15m-high bronze Buddha.

A fascinating and beautiful place, just watch out for the local deer who roam across the park – they are usually hungry!

Kyoto

Japan’s former capital doesn’t look the part initially but has some beautiful and important historic places to visit. Just look closely and you will find a temple almost everywhere. A hop-on, hop-off bus tour is a great way to explore the city. Amongst the many treasures, there are some must-see highlights:

The Temple of the Golden Pavilion

The Ryoanji zen garden is a place for contemplation

And the Fushimi Inari shrine, a short train ride outside the main city, with its plethora of vermillion torii (temple gates) to wander through.

Hiroshima

A city with an horrific history, Hiroshima has recovered to become a modern, cosmopolitan city. The Peace Park and museum give a balanced history of the atomic bombing and, while it is a difficult place to visit, is also a peaceful and contemplative place.

The Peace Park has a non-eternal flame which will be extinguished when the last nuclear weapon on earth has been decommissioned.

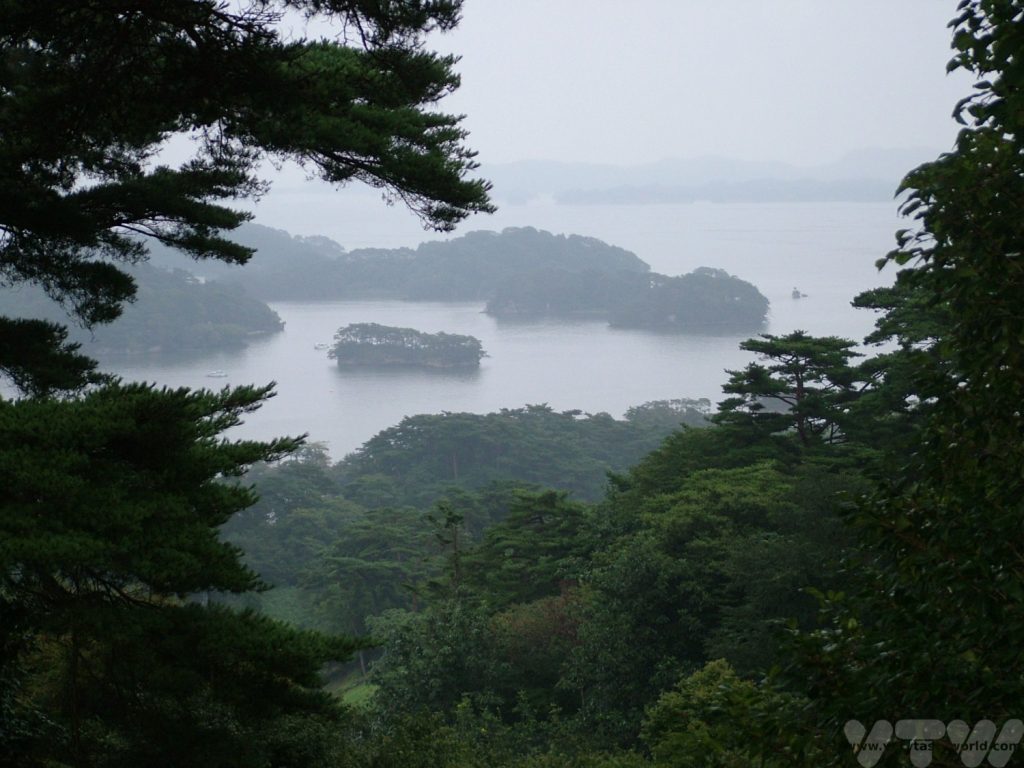

Don’t forget to visit the island of Miyajima which is a short journey away. Tours are available from Hiroshima. You can see the iconic Torii gate in the sea, one of the top three iconic views of Japan.

Japan Alps

If you enjoy hiking in splendid countryside, the Japan Alps are ideal. Kamikochi and Norikura Kogen are delightful places to visit.

And the gassho houses of rural Honshu offer a fascinating glimpse into traditional rural life. You can stay in a farmhouse in Ainokura.

Staying in a gassho you are likely to try the local produce – fresh river fish and mountain vegetables.

There are a number of tours available to visit these delightful villages.

Hokkaido – The Northern Island

Sapporo

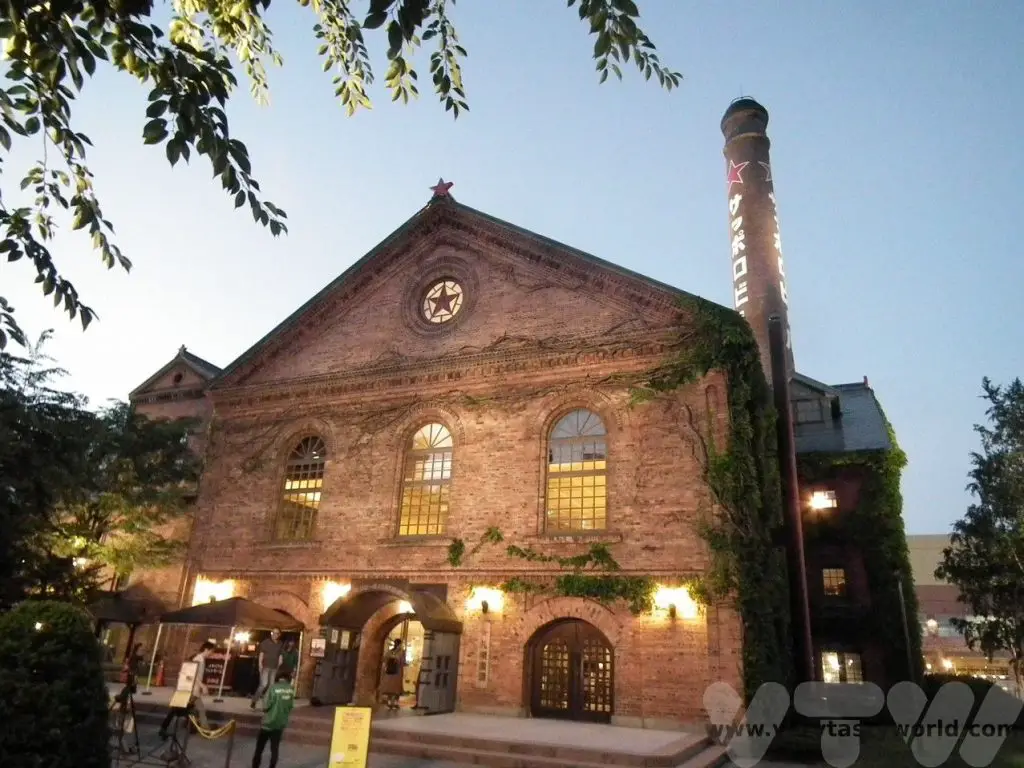

The capital of Hokkaido is a laid back city. It has a snow festival every winter and you can view amazing snow sculptures in the extensive city park.

You can visit the Sapporo beer museum to learn about – and taste – some of Japan’s most famous beers.

A day trip from Sapporo to Yoichi is a great opportunity to try Japanese whiskey at the Nikka distillery – the area has a similar soil type and climate conditions to Scotland. There are freebie samples in the tasting hall too!

Hakodate

If you like seafood, particularly crab, head to Hakodate where you can enjoy crab for breakfast, lunch and dinner. Rice bowls are available for good prices at the market.

Hokkaido also has some wonderful countryside to explore – the Akan lake district is beautiful and the island is home to many red-crowned cranes.

Kyushu – The Southern Island

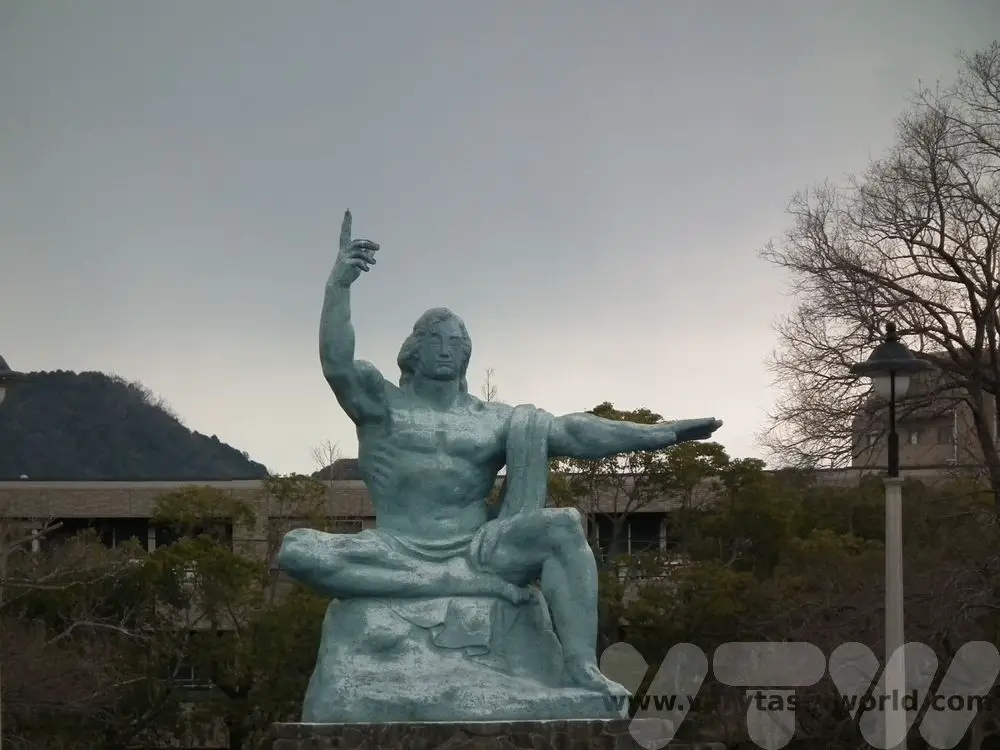

Nagasaki

Another city famous for its history Nagasaki was the port city through which Japan traded with the outside world during the Tokugawa shogunate between 1639 and 1859 period, when the rest of the country was effectively isolated.

A major shipbuilding centre, it was the target for the second atomic bomb that was dropped on Japan. Like Hiroshima, the city has recovered and also has a museum about the bombing, with a significant emphasis on the call to ban nuclear weapons.

Nagasaki is famous for its champon noodle dish, inspired by Chinese cuisine. The noodles are boiled in the soup and hence acquire some its rich flavour.

Kagoshima

This is a lively city in the shadow of the very active Sakurajima volcano.

Sakurajima is still very active.

Kagoshima is famous for its kuro buta – black pork, from a specific breed of pig. The tonkotsu ramen, with its creamy umami broth and topped with pork slices, is sublime.

Beppu

Sometimes described as the Las Vegas of Japan (it isn’t really), Beppu is a resort town well known for its onsen hot springs.

A place to relax and unwind, as well as to visit the “Hells” – thermal hot springs each of which has a specific theme.

Yakushima

A ferry ride away from Kagoshima this small island is a wonderful place to explore. It was the inspiration for the setting of Hayao Miyazaki’s Princess Mononoke anime.

The cuisine on Yakushima is fresh, local seafood and vegetables and is delicious.

Shikoku

The fourth largest of Japan’s major islands Shikoku offers an opportunity to experience a more rural Japan. It has a pilgrimage route, dedicated to the 9th-century monk Kukai, which comprises 88 Buddhist temples over a 1200km route.

Okinawa

Okinawa is an archipelago south of the main islands and offers a very different view of Japan. It’s sometimes known as the ‘Hawaii of Japan’ and is off the beaten track. It has broad, sandy beaches and crystal clear water as well as a great natural beauty. It also has its own cuisine which offers a variety of dishes that are a contrast to mainland Japanese food.

Japan has so many other amazing places to visit, this post could have gone on for several more pages. Hopefully this has offered a taste of the many wonderful things Japan can offer. We can’t recommend a visit highly enough. We’re already planning our next trip…

Related Posts You May Enjoy

- Recipe: Simmered Shiitake Mushrooms

- How to Use Public Transport in Japan

- RECIPE Oyakodon Donburi

- Planning a Trip to Japan

- The Makanai: Cooking for the Maiko House

- Setsubun Food – Bean Throwing Day

- The Gassho Farmhouses of Rural Japan

- Recipe: Japanese Simmered Pork Belly – Buta no Kakuni

- RECIPE: How to Make Umeboshi

The Makanai: Cooking for the Maiko House

Director: Koreeda Hirokazu(是枝 裕和)

From the manga by Aiko Koyama

Starring: Nana Mori,Natsuki Deguchi,Aju Makita

Cuisine: Japanese

Country (of film origin): Japan

TV Rating: 9/10

Foodie Rating: 9/10

Review: Cuisine and culture combine in an emotional and educational entertainment about Kyoto life, friends, futures and food.

There’s a line in anarchic 80s British TV show The Young Ones when punk student Vivyan, talking about a TV show, yells, “It’s so bloody nice!” Whereas his character despised feelgood TV, you just can’t help falling for the voie de vivre while watching The Makanai, a charming and quite delightful Netflix series. Based on the manga Kiyo in Kyoto: From the Maiko House by Aiko Koyama, the teleplay is written and partly directed by Koreeda Hirokazu, whose Palm d’Or winning film Shoplifters ( 2018) takes a very different perspective on food and society.

Kiyo Nozuki (Nana Mori) and Sumire Herai (Natsuki Deguchi) are two best friends from Aomori prefecture who leave the cold northern region of Japan to become maiko in Kyoto. Maiko are apprentice geiko (the Kyoto term for geisha) and the sixteen year olds will join the Saka establishment and train in the arts of traditional singing and dancing. This is a whole new world for the pair as they need to learn the etiquette and the correct way to address their superiors and other maiko in their house – the geiko are ‘mother’ and their maiko companions are referred to as ‘sister’. It’s hard work and the daily routines preparing for the coveted roles are tough as they train and practice new skills.

In fact, it’s so tough that Kiyo just can not meet the requirements of the training and the mothers sadly inform her that she will not become a maiko. However, they recognise that she is a hard worker and a great cook, so Kiyo stays in the maiko house to become a worthwhile addition to the business as a makanai. It is her job to purchase all the food and prepare delicious meals for the household. So she dedicates herself to getting up early in the morning to embark on shopping trips to familiarise herself with market vendors so that she can obtain the necessary ingredients.

It is fortunate that her grandmother taught her to cook because the plethora of delicious dishes that Kiyo can produce is awesome in its variety and each meal looks utterly delicious. Fortunate for foodie viewers the creation of these dishes is shown in vignettes which will not only have your mouth watering, they will provide lots of inspiration for future recipes.

And so we follow Sumire’s journey as she becomes a talented apprentice with huge potential to progress to becoming a respected maiko and Kiyo, who could have been immensely jealous of her friend’s success, is unwaveringly supportive and genuinely happy in her new role.

Traditional events, integral to Kyoto culture and cuisine, are depicted through the whole series. Perhaps the most significant event occurs in episode seven by which time Kiyo is fully established as the makanai. The geiko and maiko ladies start the new year by attending a formal ceremony. But Sumire falls ill and loses her appetite, and it is down to Kiyo to cook up some comfort food. She is advised to produce a traditional Kyoto based remedy – udon noodles in broth – which requires distinct ingredients and implementation that the exceptional cook must learn to create.

Her regular market proprietors advise on the best venues in obscure parts of town to get the required ingredients to make an exemplary dashi (broth). A prodigious bonito flake creator marks the beginning of her quest and an exemplary kombu (kelp) nori (seaweed) producer introduces her to perfectly dried sheets of seaweed. This is as much a learning experience for the viewer as it is for our protagonist, although we can but dream of such delicacies.

The Makanai: Cooking for the Maiko House is a series unlike anything you have ever seen before. It is so full of companionship and understanding you genuinely take delight in the niceness portrayed; it’s as sweet as some of the immaculate desserts that Kiyo creates. When a series makes you want to have a delicately shaped egg sandwich and deep fry the crusts for an additional snacky surprise you know you have seen something different and delightful.

This is also a show about food and cookery in that the creation of the meals are an important element the story. And therein lies the show’s only real problem – you want there to be an ingredients list before each episode so you can make the dish afterwards. We’re definitely going to try some of the goodies that the maiko enjoyed. Be warned though – make sure you eat before watching or face inevitable pangs of hunger…

Related Posts You May Enjoy

- The Makanai: Cooking for the Maiko House

- Film Review: Bao (2018)

- Film Review: Jadoo (Kings of Curry 2013)

- Film Review: Ramen Girl (2008)

- Film Review: Nina’s Heavenly Delights (2006)

- Film Review: Chocolat (2000)

- RECIPE Oyakodon Donburi

- Zero Waste Recipes Before Your Holiday

- RECIPE: Vegetable Biryani Tamil Nadu Style

- RECIPE: Vegan Wild Garlic Pesto

- Recipe: Venetian Pasta Sauce

- RECIPE: Biryani Raita Recipe

- RECIPE: How to Make Costa Rica’s Gallo Pinto

- Recipe: Japanese Simmered Pork Belly – Buta no Kakuni

- RECIPE: How to Make Umeboshi

Setsubun Food – Bean Throwing Day

Feb 3rd is Setsubun in Japan. Which means that it’s mame maki, or bean throwing, day. Setsubun is one day before Risshun – the first day of spring in the lunar calendar. It’s not considered to be the official new year, which is celebrated on the 1st January, but rather a new start. There are various ceremonial activities associated with the festival, including setsubun food.

Traditionally people throw roasted soy beans (fuku mame) at home, with the shout of ‘oni wa so to’ (get out demons!) and ‘fuku wa uchi’ (come in happiness!) Sometimes the beans are just thrown out of the front door but they may also be thrown at a family member wearing an oni – demon – mask. If people eat the number of fuku mame that’s equal to their age it’s believed that they will be healthy and happy for the year ahead.

Bean throwing ceremonies also take place at shrines across Japan. The Senso-ji temple in Asakusa will have thousands of visitors arrive to take part. Celebrities and sometimes sumo wrestlers are known to turn up to some of the events.

Setsubun Food Tradition

Over the years a foodie setsubun tradition has developed. This is thought to have originated in the Kansai region, in Osaka (always a great place for foodies!) and has become more popular throughout Japan over the years.

It involves eating ehomaki (good luck direction rolls) which are sushimaki rolls that haven’t been cut up. The idea is to eat the roll while facing in the lucky direction. You will need a compass because the direction is quite specific. Last year was the year of the rabbit and therefore the direction was south-south-east. 2024’s direction is east-northeast for maximum luck.

We often make maki rolls using a bamboo rolling mat. They are the easiest sushi to make, even for clumsy cooks such as we. When you’ve had a go at making nigiri or gunkan sushi you realise why it takes 10 years to train as a sushi chef!

There are lots of options for ehomaki filling. One of our favourites is maguro tuna with spicy kimchi and mayo.

- Recipe: Simmered Shiitake Mushrooms

- How to Use Public Transport in Japan

- RECIPE Oyakodon Donburi

- Planning a Trip to Japan

- The Makanai: Cooking for the Maiko House

- Setsubun Food – Bean Throwing Day

- The Gassho Farmhouses of Rural Japan

- Recipe: Japanese Simmered Pork Belly – Buta no Kakuni

- RECIPE: How to Make Umeboshi

- RECIPE Oyakodon Donburi

- Zero Waste Recipes Before Your Holiday

- RECIPE: Vegetable Biryani Tamil Nadu Style

- RECIPE: Vegan Wild Garlic Pesto

- Recipe: Venetian Pasta Sauce

- RECIPE: Biryani Raita Recipe

- RECIPE: How to Make Costa Rica’s Gallo Pinto

- Recipe: Japanese Simmered Pork Belly – Buta no Kakuni

- RECIPE: How to Make Umeboshi

The Gassho Farmhouses of Rural Japan

It’s not often that we use the word ‘unique’ because very often things described as such usually aren’t. Unique, that is. But there are some villages in rural Japan that are the only examples of their kind and they offer a fantastic glimpse into traditional life in the Japanese countryside.

The historic mountain villages of Shirakawa-go and Gokayama have been designated as UNESCO heritage sites and were historically quite isolated from the rest of the world. The villages Ogimachi in Shirakawa-go, and Ainokura and Suganuma in the Gokayama region are located in central Honshu, on the Shogawa river valley, across the borders of the Gifu and Toyama Prefectures.

Ogimachi is probably the most famous of the villages and is known for its light-up events, where the whole village turns their lights on in winter-time and visitors come from far and wide to marvel at the beauty of a snowy wonderland. These are scheduled events and hugely popular. Reservation is essential, not only for staying in the village but also for attending the viewing and some transportation options.

Initially when planning our winter trip we thought that Ogimachi would be the obvious place to visit but unfortunately everybody else thinks that too. It was impossible to find accommodation in this lovely village, even when trying to book several months in advance. But we had a Plan B which worked very well indeed. Ainokura is smaller and quieter but similarly delightful.

Getting to Ainokura in Rural Japan

We had been staying in a business hotel in the lovely city of Kanazawa on the western coast of Japan and, as we planned to return there, left our main luggage at the hotel and just took an overnight bag with us. We then caught the shinkansen (bullet train) from Kanazawa to Shin-Takoaka. It is possible to catch a bus to Ainokura from Shin-Takoaka – the journey takes just over an hour or so – but we caught possibly the cutest train ever to Johana and caught our bus from there.

Ainokura can also be reached from Toyama. The shinkansen goes to Toyama and it’s possible to catch a bus from there. It is feasible to visit the village as a day trip from both Takoaka and Toyama but we recommend staying overnight.

Our bus to Ainokura left from Johana station and we embarked on a pleasant journey through the Japanese countryside. A short walk from the main road took us into the village.

A word of warning: If you are visiting during the winter the area can experience a lot of snowfall – 2-3 metres on occasion. This may mean that occasionally buses can’t get through and are delayed until the roads can be cleared. It’s worth bearing this in mind when planning your onward journey.

Staying in a Gassho Farmhouse

The farmhouses are called ‘gassho’ which means ‘joining hands in prayer’ due to their very steeply pitched thatched roofs. Because the area experiences such heavy snow in winter, the roof design ensures that snow falls off the building quickly and this helps prevent the structure being crushed by its weight.

The houses have three or four levels – the top levels are not living areas but used for various industrial or farming purposes, such as making washi paper or rearing silkworms.

The front and back have a large gable with windows to let the light in.

We booked a room at Yomoshiro ryokan, a delightful family run house.

On arrival we took off our shoes and were offered an array of indoor slippers to wear. This is very common in all Japanese households, it’s considered very rude to wear outdoor shoes inside a house.

Our hosts were lovely and very welcoming. We were offered a cup of warm tea and a biscuit in the living area.

The living area has a sunken fire with a kettle suspended above the embers. The room was warm and toasty.

Our room was in traditional style with tatami (reed) mat and futon bedding on the flooring. Usually the bed is laid out while you are enjoying dinner.

The bathroom and toilet were shared with other guests and one thing that you need to remember in Japan is to change your indoor slippers for bathroom slippers when you use the bathroom or toilet. And change them back – it is really easy to forget to change the slippers back and walking on the tatami in your bathroom slippers is like walking inside in your outdoor shoes.

Exploring the Village

We visited the day that our hosts reopened their accommodation after the new year holiday so unfortunately some of the attractions in the area weren’t yet open. There is a museum of traditional industries which demonstrates the paper making and silk activities of the region.

The village also has a folk museum that showcases traditional utensils, tools and musical instruments from the region.

There are a number of walks in the area. One of these is essential – a viewing area close to the village entrance where you can climb up the hillside to take that perfect shot of the village, nestled amidst the mountains.

Back to the Gassho for Dinner

The costs of our stay included dinner and breakfast and this was a highlight of the visit as the food on offer was locally sourced, some even grown by our hosts. We dined with the other guests in the living area.

Our home-cooked dinner was utterly delicious. Char, a fish a bit like a trout, was salted and roasted on a spit in the fire.

We were also served koi sashimi, vegetable tempura and a home-grown spaghetti squash, mountain greens, and simmered bamboo shoots, mushrooms and sweet potato.

Rice accompanied the meal and we also enjoyed some local sake.

After dinner we were entertained with a documentary about the villages and then our hosts played some music using traditional instruments.

A lot of these are percussion, notably the sasara which comprises many wooden clappers which are strung together.

A Cosy Night’s Sleep

At bedtime we were provided with hot stones to put into our futons.

These stones had been heated in the fire and were placed inside ceramic boxes then wrapped in a thick cloth.

These were better than any hot water bottle we’d ever used, they retained the heat so well – they actually felt as though they were getting warmer through the night.

Breakfast the following morning was a traditional Japanese meal and also delicious. There were lots of fresh vegetable dishes, rice and miso soup.

We were given the choice of a raw or boiled egg. We always choose raw egg. You mix it into the rice, which partially cooks the egg, add a bit of soy sauce to your taste and then scoop up the flavourful mixture with a piece of nori seaweed. You usually get a sour and salty umeboshi plum – a real wake-up call!

Staying in a gassho is a delightful way to spend time in rural Japan and is highly recommended. But… make sure you plan your trip and book early!

Related Posts You May Enjoy

- Recipe: Simmered Shiitake Mushrooms

- How to Use Public Transport in Japan

- RECIPE Oyakodon Donburi

- Planning a Trip to Japan

- The Makanai: Cooking for the Maiko House

- Setsubun Food – Bean Throwing Day

- The Gassho Farmhouses of Rural Japan

- Recipe: Japanese Simmered Pork Belly – Buta no Kakuni

- RECIPE: How to Make Umeboshi

Recipe: Japanese Simmered Pork Belly – Buta no Kakuni

Japanese simmered pork belly, known as buta no kakuni, is a rich, indulgent dish that is sweet, savoury, sticky and utterly sumptuous. Pork belly is a really fatty cut of meat but fat means flavour and the process of cooking the pork for a long time ensures that a lot of the fat will melt away. Any fat that remains is soft and juicy.

In Japanese, buta means pork and kakuni derives from two longer words: kaku- to cut into cubes and ni – simmer.

It is traditional to serve kakuni with a drop of Japanese mustard called karashi (辛子 or からし). Karashi is a bit darker yellow than most other mustard. It does not really have much acidity in it (unlike other mustards) and very hot. It is perhaps closest to hot English mustard, which is a good substitute.

How to Make Buta No Kakuni Japanese Simmered Pork Belly (Serves 2)

Ingredients

Portion of pork belly per person (allow around 150-200g per person depending on how hungry you are)

Water

Stock cube – dashi stock if possible or you can make your own

2 spring onions, sliced into 2-3cm chunks plus another for garnish

2 inches of ginger, peeled and cut into strips

16 tbs (1 cup) of water

4 tbs (1/4 cup) soy sauce

4 tbs (1/4 cup) cooking sake (if you can’t get sake, white wine will be a good substitute)

4 tbs (1/4 cup) caster sugar

4 tbs (1/4 cup) mirin (if you can’t get mirin, add a little more sake and sugar)

Generous splash of rice vinegar (we like this to counterbalance some of the sweetness of the dish)

Method

Place the pork belly in a frying pan and sear on both sides for a couple of minutes.

Place the pork belly in a pot and cover with water. Add the stock cube, spring onion and ginger. Turn on the heat and bring the water up to a simmer. Simmer the pork for 2 hours or until nice and tender. Alternatively, you can do as we do and use a pressure cooker. Just prepare the pork as above and cook at pressure for 40 minutes.

When the pork comes out it should be wonderfully soft and close to falling apart (but not actually falling apart). Cut the pork into chunks – about 2cm length. We also decided to cut off the rind at this stage.

Don’t forget to keep the stock – it will make a wonderful base for ramen noodles or soup. You can pop it into the freezer if you’re not going to use it immediately.

Put the water, soy sauce, sake (or wine), mirin and sugar into a pan and bring to the boil.

Carefully place the pork chunks into the pan and press down so that the sauce completely covers them.

(In retrospect we should have put the pork into a deeper pan – a casserole dish – because the sauce did splutter a lot and because there was sugar in it, it stuck to our hob which made clearing up a bit of a nightmare!)

Reduce the sauce until it has almost become a paste – it will have coated the pork and caramelised on the underside. It will look glossy and luscious.

Serve atop plain white rice garnished with chopped spring onion. It is often accompanied with a splodge of karashi. We like adding some pickled ginger as well.

- RECIPE Oyakodon Donburi

- Zero Waste Recipes Before Your Holiday

- RECIPE: Vegetable Biryani Tamil Nadu Style

- RECIPE: Vegan Wild Garlic Pesto

- Recipe: Venetian Pasta Sauce

- RECIPE: Biryani Raita Recipe

- RECIPE: How to Make Costa Rica’s Gallo Pinto

- Recipe: Japanese Simmered Pork Belly – Buta no Kakuni

- RECIPE: How to Make Umeboshi

- Recipe: Simmered Shiitake Mushrooms

- How to Use Public Transport in Japan

- RECIPE Oyakodon Donburi

- Planning a Trip to Japan

- The Makanai: Cooking for the Maiko House

- Setsubun Food – Bean Throwing Day

- The Gassho Farmhouses of Rural Japan

- Recipe: Japanese Simmered Pork Belly – Buta no Kakuni

- RECIPE: How to Make Umeboshi

RECIPE: How to Make Umeboshi

A typical Japanese breakfast will comprise of a bowl of rice, some grilled fish and pickles accompanied by a bowl of miso soup. What a lovely way to start the day. And at the Japanese breakfast table you will often come across a bowl of pink, wrinkly fruit, roughly the size of an apricot.

These are umeboshi, incredibly sour and salty ume fruit, which are like small plums or apricots, and are absolutely guaranteed to wake you up. They are also reputed to be a hangover cure, especially good if you are a salaryman who has had a late night out in the city. Or tourists who have had a late night in the city which involved chatting with all sorts of very interesting people in random bars and drinking quite a lot of booze.

Beware the stone, especially if you have a hangover.

Umeboshi are tsukemono, literally “pickled things” which brined and therefore fermented, so they will last for ages. Some will even last decades. If they turn black, they should be chucked. We always bring some back from our trips to Japan and rationed them so had some in our fridge for about 5 years – they were still pink and wrinkly and utterly delicious. Most Japanese meals have tsukemono as an accompaniment but umeboshi are most often eaten at breakfast. They are also used in onigiri (rice balls) as a flavouring and can be converted into a paste to add plentiful salty/fruity flavour to a variety of dishes.

Some Japanese households make their own umeboshi. If you are lucky enough to be offered these, don’t be polite. Well, do be polite because that would be the right thing to do, but don’t hesitate to take your host up on their offer. Home-made umeboshi are absolutely delicious. The pink colour derives from red shiso – also known as perilla – which is a herb added during the pickling process. Shiso is a very common herb used a lot in Japanese cuisine. Green shiso is often the herb that garnishes a sushi platter.

It is possible to make sort-of-umeboshi in western countries. The ume fruit is not usually available, but you can have a bash using plums and salt.

We treated ourselves to a Japanese pickle press a while ago but it should be possible to make umeboshi using a wide-mouthed jar, just as long as you have something heavy that will fit inside the jar to weigh the plums down and a utensil that can extract them (tongs should be fine) as you will need to take them in and out of the jar after the fermentation.

We use plums from our allotment. They have the delightful name Warwickshire Droopers. The great thing is that we can assess how ripe our plums are and pick them. This year the plum tree has been very generous. If you don’t have a plum tree your local market or greengrocer may well have a variety of plums for you to choose from.

You want the plums to be ripe but not over-ripe, they need to have a degree of firmness.

How to Make Umeboshi

Ingredients

Plums – enough to fill your container but leaving enough space to add a weight. If using a press, make sure the press can close and provide enough pressure.

Salt – 8% of the weight of the plums. Try not to use table salt, as this contains anti-caking agents. We prefer Himalayan pink salt but any pure salt will be fine.

2 red shiso leaves (optional)

Method

Wash your plums and pat them dry. Weigh the plums.

Measure out your salt – the total should be around 8% of the plum weight. This is a lot of salt but most of it will leach into the juice during the pressing process.

Massage the salt into the plums

Place in the press. Add the shiso/perilla leaves if you are using them.

Attach the lid and screw the pressure plate down as far as it will go. If you are using a jar, put a clean weight (you can put a weight inside a plastic bag) that puts pressure on the plums.

This ferment doesn’t use a brine. The pressure of the weight will release juice from the plums.

Leave in a cool, dark place for 2-3 weeks. Check the plums occasionally. You will start to see juice appearing in the bottom of the press.

(As with all ferments, if you ever see any mould on the fruit you should throw it away as the spores could cause illness if you consume the plums. It is unlikely that mould will develop with an 8% salt mix as that is lot of salt.)

The next step requires a bit of luck with the weather. Ideally you want a warm, sunny day. In fact, you need three warm, sunny days.

On your sunny day, remove all the plums and place them on a mat, or some kitchen paper, in the sunshine to dry. Place them back in the juicy brine at the end of the day.

Repeat for a further two days. They don’t need to be consecutive days but it would be helpful if you can dry the plums over the course of a week.

After the third day, you can place the plums in a jar or a plastic container, or even a plastic bag. They will last for months and months. That’s if you don’t scoff them…or have too many hangovers to cure!

Save the Brine!

We hate food waste so we have devised a way to re-use the salty plum juice brine.

We use it to pickle ginger.

Peel the ginger and cut into matchsticks.

Place them in a jar and cover them with the brine. After a couple of weeks they will be deliciously sour and salty. We use them to add some zing to rice and noodle dishes or as a garnish.

Actually, we have been known to open the jar and sneak a matchstick or two for a quick snack.

Related Posts You May Enjoy

- RECIPE Oyakodon Donburi

- Zero Waste Recipes Before Your Holiday

- RECIPE: Vegetable Biryani Tamil Nadu Style

- RECIPE: Vegan Wild Garlic Pesto

- Recipe: Venetian Pasta Sauce

- RECIPE: Biryani Raita Recipe

- RECIPE: How to Make Costa Rica’s Gallo Pinto

- Recipe: Japanese Simmered Pork Belly – Buta no Kakuni

- RECIPE: How to Make Umeboshi

Osaka Restaurants Japan – Kuidaore on Dotonbori

We visited Osaka (pronounced O-saka rather than o-SAR-ka) on our very first trip to Japan many years ago. We had already spent time exploring Tokyo, Hakone and Kamakura and it was following an afternoon and evening in Osaka, exploring the neon arcades and playing video games, taking silly photos in the print club booths, riding the Hep 5 big wheel and singing our socks off in a karaoke bar (where you get a private booth rather than have to sing in front of complete strangers), that we realised that we had fallen in love with Japan. The following day we visited the Dotonbori area in the Namba district and discovered Osaka’s restaurants. We decided that Osaka was our favourite place in the world.