RECIPE: Vegan Wild Garlic Pesto

Every spring we make the most of foraging for greens in the English countryside. Wild garlic is our absolute favourite and we have a fabulous recipe for wild garlic pesto. But pesto uses cheese! So we also have a recipe for vegan wild garlic pesto.

In the UK you can forage wild garlic for free as long as you just take the leaves, stems and flowers. All these parts are edible. We make it a rule never to take more food than we need as it’s nice to leave some for other people and also ensure that the plant will appear next year. We try to pick one leaf from each stem so as not to disturb the plant too much.

Foraging for Wild Garlic

Wild garlic is pretty easy to recognise and has a very definite garlicky smell. Pick a leaf and crush it in your hand – it has a wonderful scent.

A little later into the season lovely white flowers appear. These have a very mild garlic flavour – we use them to garnish dishes.

As with any foraging, you have to be 100% certain of what you are picking. Poisonous plants can grow near wild garlic. Arum maculatum, also known as Lords and Ladies, is very toxic. Apparently even putting the leaves into your mouth will result in an immediate burning sensation. It can grows worryingly close to the wild garlic. When it’s more mature it develops shiny arrow-head shaped leaves but when young, looks very similar to wild garlic.

Bluebells, or their white-flowered counterparts, which can also easily be confused with wild garlic’s white flowers, can also grow nearby. Bluebells are extremely pretty but also poisonous.

If you are the slightest bit uncertain, DON’T eat it!

Vegan Wild Garlic Pesto Recipe

Just like our standard recipe our vegan wild garlic pesto isn’t precise. We use cashew nuts but you can also use pine nuts (and weep at the expense) or pistachios. You can use a blender to mix everything together but if you’re feeling hardcore you can use a pestle and mortar.

We use nutritional yeast as a substitute for the cheese. It’s a brilliant product that is really good for you – a great source of protein, fibre, vitamins and minerals. More importantly it has a cheesy flavour, perfect for adding that umami element to the pesto amidst the creamy cashew and heavenly garlicky scent.

Ingredients

Bunch of wild garlic leaves (around 150g)

Handful of cashew nuts (around 150g)

Generous sprinkle of nutritional yeast flakes (we recommend couple of tablespoons if you’re measuring)

Slosh of extra virgin olive oil

Squeeze of lemon

Pinch of salt

Method

Roughly chop the wild garlic leaves and place into a blender. Throw in the nuts and nutritional yeast flakes. We recommend adding the leaves first – to the bottom of the blender – so that the weight of the nuts helps with the grinding process.

To take advantage of the season we make industrial quantities and freeze it, so we can enjoy the scented flavour of spring throughout the year. We don’t add the oil, lemon and salt before seasoning but stir it in after it has defrosted.

Blend together until you get the texture you like – smooth or nutty – both work well.

If you want to freeze the pesto, decant it into containers and put it into the freezer. It will freeze well and will last many months.

If you want to eat the pesto straight away (or store it in the fridge for a couple of days) add the oil, lemon juice and salt.

The great thing about this recipe is that is so easily adaptable – you can mix and match ingredients. It’s the underlying gentle garlicky flavour that the wild garlic leaves produce that make this such a brilliant pesto. We’ll be foraging and freezing for as long as the season lasts.

Related Posts You May Enjoy

- RECIPE: How To Make Elderflower Champagne

- RECIPE Oyakodon Donburi

- Zero Waste Recipes Before Your Holiday

- RECIPE: Vegetable Biryani Tamil Nadu Style

- RECIPE: Vegan Wild Garlic Pesto

- Recipe: Venetian Pasta Sauce

- RECIPE: Biryani Raita Recipe

- RECIPE: How to Make Costa Rica’s Gallo Pinto

- Recipe: Japanese Simmered Pork Belly – Buta no Kakuni

RECIPE: Biryani Raita Recipe

There are many cuisines around the world that use yoghurt-based dips or sauces to accompany particular dishes. Tzatziki is a Greek dish which incorporates cucumber and herbs into a Greek yoghurt. Salatat Khyar is an Arabic salad which is similar to tzakziki in that it uses cucumber and mint with the yoghurt but can be eaten as a standalone salad. And then there’s raita, often used in Indian cuisine as an accompaniment to ‘cool’ the spiciness of a main dish. This biryani raita recipe is simplicity itself to make and really delicious.

Yogurt is ideal to counteract the heat of chillies in any dish it accompanies. There’s a protein called casein which is found in dairy products. It binds to the active component of chillies which is called capsaicin and is the main cause of the burning sensation in the mouth. The casein helps soothe the burn. If you eat a spicy chilli, a drink of milk will help quash the heat far better than water.

(The combination of chilli and cheese in Bhutan’s national dish is cleverly designed to be spicy but the intense heat is tempered by the cheese.)

Raita uses cucumber but it can also have other vegetables such as onion and carrot, often diced. This dish can easily be adapted to incorporate different vegetables or even spices. If you wanted to add a warm earthiness, chuck in a teaspoon of cumin. Or add a touch of fire with a teaspoon of chilli or paprika. Harissa is a nice addition for a Middle Eastern dish. Similarly, you can vary the herbs – mint is a lovely alternative to the coriander or you can just add both in.

Our biryani raita is fantastically flexible in accompanying so many different types of dish.

Biryani Raita Recipe

Ingredients

3 heaped tbs plain natural yoghurt

2 garlic cloves (use 1 if you’re not so keen on garlic or are planning on kissing someone later on in the day)

Juice of half a lemon

Half a cucumber

2 spring onions (green onions)

Bunch of coriander/cilantro (mint also works really wall, or combine the two)

Pinch of salt. We particularly like crystal salt rather than table salt

Method

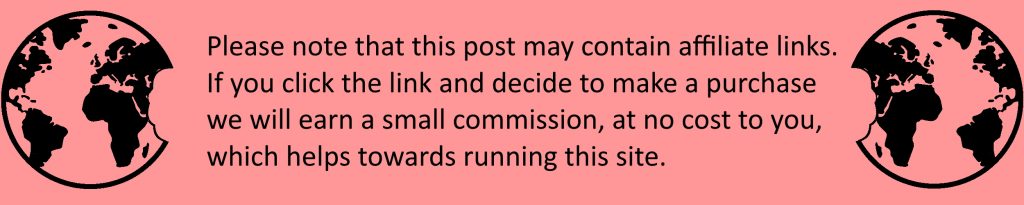

Grate the cucumber.

Gather up grated cucumber and squeeze the water out.

If you wish you can wrap the grated cucumber in a tea towel to absorb the rest of the water. It’s important to get as much water out of the cucumber as possible to avoid the raita becoming watery.

Finely chop the spring onions and coriander.

Place yoghurt in a bowl. Add the cucumber, spring onions and coriander.

Grate the garlic into the bowl – we find that a microplane grater is perfect for this. Our you could use a standard garlic press.

Squeeze the lemon to extract its juice, making sure that none of the pips end up in the mixture, and add the salt.

Mix together.

Ready to serve.

This works brilliantly to accompany a biryani, and cool it down if it’s particularly chilli hot.

Or a delicious dollop as a great accompaniment to felafel in a wrap.

Or to accompany a Middle Eastern mezze. Here with home-made dolma (stuffed vine leaves), baba ganoush (aubergine dip) and tabbouleh (cous cous herb salad).

Related Posts You May Enjoy

- RECIPE: How To Make Elderflower Champagne

- RECIPE Oyakodon Donburi

- Zero Waste Recipes Before Your Holiday

- RECIPE: Vegetable Biryani Tamil Nadu Style

- RECIPE: Vegan Wild Garlic Pesto

- Recipe: Venetian Pasta Sauce

- RECIPE: Biryani Raita Recipe

- RECIPE: How to Make Costa Rica’s Gallo Pinto

- Recipe: Japanese Simmered Pork Belly – Buta no Kakuni

A Chiang Rai Temple and A Country Retreat

Sometimes it’s possible to visit a place without actually going to the place itself. If that makes sense? This happened on our trip to northern Thailand. We had spent some time in Bangkok and Chiang Mai before heading towards the city of Chiang Rai. But somehow we didn’t quite manage to visit the city itself. Having driven up from Chiang Mai, our first stop was a famous Chiang Rai temple – The White Temple – followed by a lovely couple of days exploring the local countryside.

Chiang Rai Temple – The White Temple

It’s located about 13 kilometres south of Chiang Rai city and we can honestly say it’s one of the most bizarre buildings we have ever visited.

The temple itself was conceived and designed by Thai artist Chalermchai Kositpipat and built on an enormous scale, designed in the style of a Buddhist temple. Kositpipat also supervised the construction of this remarkable building. Although it bears a strong resemblance to ancient temples of the region, it is a modern structure which opened in 1997.

The building also has ornate naga serpents, supernatural creatures that are part human, part snake, which typically decorate Buddhist temples and are revered throughout the region.

You cross the Bridge of the Cycle of Rebirth…

…passing by the fearsome guardians…

…over the lake of the damned souls…

…in order to reach heaven.

It is possible to go inside the temple, known as the ubosot, but, sadly, you are not allowed to take photos in there. We absolutely respected this, but it’s a shame because it contains the most astonishing bright and colourful murals. They combine Buddhist imagery with all sorts of modern historical and cultural icons – everything from Spider-man to Doraemon and Hello Kitty! The theme that pervades the White Temple is the conflict between good and evil in the world. You could spend hours enjoying the details, spotting all sorts of characters.

Chiang Rai’s White Temple Grounds

The temple itself was designed to be white to represent purity; a conscious choice to contrast with the temples throughout Thailand which are typically decorated in gold. Kositpipat apparently considered gold to be a colour for people who coveted evil thoughts and deeds. So it is the bathrooms that are decorated in a gorgeous gleaming gold. Possibly the most ostentatious toilets in the world!

Even the traffic cones and trees are bizarrely decorated!

Kositpipat didn’t want money to be a consideration for visitors, so when we visited entrance was free. However, these days there is a nominal charge that is used towards maintaining the temple and gardens. Which is fair enough.

A Rural Retreat

Having visited the Chiang Rai temple we then headed out towards the hills.

We were staying at the delightful Bamboo Nest, a rural retreat in the countryside. When you hear the phrase ‘rural retreat’ it often recalls images of luxury spas in pristine grounds but this was the opposite – a retreat much more suited to our tastes.

We stayed in a simple bamboo hut with thatched roof, which had no electricity and a wonderful view.

Dining was in a communal area where we enjoyed freshly cooked local meals with other guests. There was electricity available via a generator in this area which enabled the charging of phones and cameras and it also powered a fridge which conveniently contained cold soft drinks and beer, which you could purchase on an honesty basis. It was incredibly quiet and peaceful and a complete contrast to the hubbub of Thailand’s cities.

The Bamboo Nest team arranged our transportation to this remote site and will organise pickups if needed. Just get in touch directly to make a booking. We met Nok outside the White Temple and climbed into her 4WD, a vehicle that was most definitely essential for the area which we discovered as the car climbed higher and higher up the mountainside. The final leg of the journey was incredibly steep, muddy and occasionally slippery – a challenge even for a sturdy 4WD.

A Hike to the Hill Tribes

The main purpose of our visit was to enjoy some hiking in the area and to meet the local hill tribes. The hosts at Bamboo Nest can arrange a variety of excursions, either on a guided or self-guided basis, and we enjoyed a lovely long walk with Noi. It was initially a little disconcerting when he picked up a machete just before we headed out, but the walk was to take us through the mountainside forest and at times we would need to cut our own path. The treks offered are truly off the beaten track.

Thailand is hot and humid and occasionally rainy, so we had some slippery moments, particularly descending some of the steeper hills. It’s worth making sure you have good shoes and waterproofs as well as a change of clothing, just in case it rains and gets muddy.

The Chiang Rai area is home to a number of hill tribes, including the Akha and Lahu peoples. Hill tribes are ethnic minority groups who have settled in the region, living in a plethora of villages that are scattered across the mountains. The communities can be quite large or may comprise just a few families living together. Some of the villages are set up to receive tourists but Noi and Nok know the local people well, so we were able to visit a non-tourist village which gave us a much more personal and insightful experience.

After a couple of hours hiking we arrived at one of the villages of the Lahu tribe. The homes are constructed on stilts and have adjacent buildings where the farm animals reside.

We were invited into a house to join a family where we helped prepare lunch.

The houses have an open fire inside the main living area. River fish was ponassed onto sticks and cooked directly over the fire.

Bamboo stalks are segmented and hollow, so another part of meal was actually cooked inside these: Add sticky rice and water to a bamboo stalk, place it over a fire for a few minutes and… yummy sticky rice!

Pour some water into a stem, add a teabag, place over the fire and a few minutes later… a ‘pot’ of tea! Best of all was the egg – crack a couple of eggs, add some herbs, pour the mixture into the bamboo stalk, shake a bit, place over a fire (you guessed it) and a few minutes later… delicious cylindrical omelette.

We then enjoyed a longboat ride along the Mae Kok river to visit the hot springs.

Some of the land in the area has been given over to commercial agriculture so it was also possible to walk to visit the local plantations. We could see bananas…

Pineapples…

And tea.

There were also some lovely waterfalls in the area.

Each night a bonfire would be lit at Bamboo Nest and we could chat with the other guests and watch the glow of the fireflies flitting through the forest.

From the ostentation of the Chiang Rai temple to the simplicity of the remote hills of the Mae Bok basin, we couldn’t have had a more contrasting experience in this region of northern Thailand.

We just didn’t have time to visit Chiang Rai itself!

Related Posts You May Enjoy

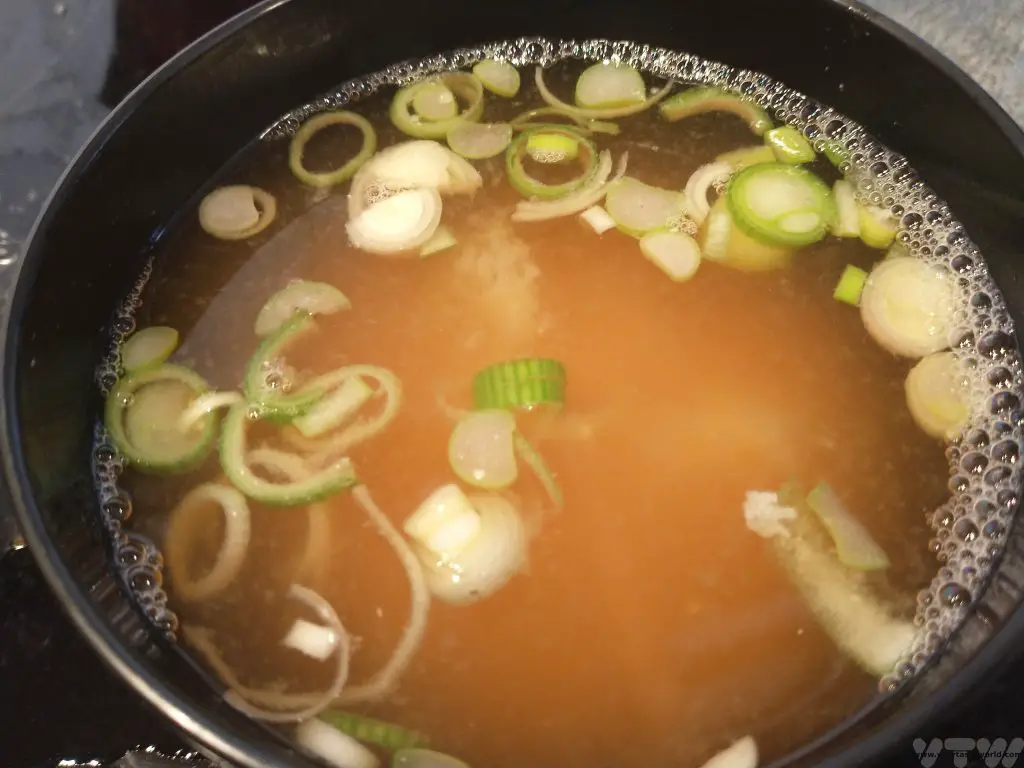

Recipe: Japanese Simmered Pork Belly – Buta no Kakuni

Japanese simmered pork belly, known as buta no kakuni, is a rich, indulgent dish that is sweet, savoury, sticky and utterly sumptuous. Pork belly is a really fatty cut of meat but fat means flavour and the process of cooking the pork for a long time ensures that a lot of the fat will melt away. Any fat that remains is soft and juicy.

In Japanese, buta means pork and kakuni derives from two longer words: kaku- to cut into cubes and ni – simmer.

It is traditional to serve kakuni with a drop of Japanese mustard called karashi (辛子 or からし). Karashi is a bit darker yellow than most other mustard. It does not really have much acidity in it (unlike other mustards) and very hot. It is perhaps closest to hot English mustard, which is a good substitute.

How to Make Buta No Kakuni Japanese Simmered Pork Belly (Serves 2)

Ingredients

Portion of pork belly per person (allow around 150-200g per person depending on how hungry you are)

Water

Stock cube – dashi stock if possible or you can make your own

2 spring onions, sliced into 2-3cm chunks plus another for garnish

2 inches of ginger, peeled and cut into strips

16 tbs (1 cup) of water

4 tbs (1/4 cup) soy sauce

4 tbs (1/4 cup) cooking sake (if you can’t get sake, white wine will be a good substitute)

4 tbs (1/4 cup) caster sugar

4 tbs (1/4 cup) mirin (if you can’t get mirin, add a little more sake and sugar)

Generous splash of rice vinegar (we like this to counterbalance some of the sweetness of the dish)

Method

Place the pork belly in a frying pan and sear on both sides for a couple of minutes.

Place the pork belly in a pot and cover with water. Add the stock cube, spring onion and ginger. Turn on the heat and bring the water up to a simmer. Simmer the pork for 2 hours or until nice and tender. Alternatively, you can do as we do and use a pressure cooker. Just prepare the pork as above and cook at pressure for 40 minutes.

When the pork comes out it should be wonderfully soft and close to falling apart (but not actually falling apart). Cut the pork into chunks – about 2cm length. We also decided to cut off the rind at this stage.

Don’t forget to keep the stock – it will make a wonderful base for ramen noodles or soup. You can pop it into the freezer if you’re not going to use it immediately.

Put the water, soy sauce, sake (or wine), mirin and sugar into a pan and bring to the boil.

Carefully place the pork chunks into the pan and press down so that the sauce completely covers them.

(In retrospect we should have put the pork into a deeper pan – a casserole dish – because the sauce did splutter a lot and because there was sugar in it, it stuck to our hob which made clearing up a bit of a nightmare!)

Reduce the sauce until it has almost become a paste – it will have coated the pork and caramelised on the underside. It will look glossy and luscious.

Serve atop plain white rice garnished with chopped spring onion. It is often accompanied with a splodge of karashi. We like adding some pickled ginger as well.

- RECIPE: How To Make Elderflower Champagne

- RECIPE Oyakodon Donburi

- Zero Waste Recipes Before Your Holiday

- RECIPE: Vegetable Biryani Tamil Nadu Style

- RECIPE: Vegan Wild Garlic Pesto

- Recipe: Venetian Pasta Sauce

- RECIPE: Biryani Raita Recipe

- RECIPE: How to Make Costa Rica’s Gallo Pinto

- Recipe: Japanese Simmered Pork Belly – Buta no Kakuni

- Kobe Beef in Kobe – Is It Worth It?

- World’s Best Breakfasts -Breakfast of Champions!

- Recipe: Simmered Shiitake Mushrooms

- How to Use Public Transport in Japan

- RECIPE Oyakodon Donburi

- Planning a Trip to Japan

- The Makanai: Cooking for the Maiko House

- Setsubun Food – Bean Throwing Day

- The Gassho Farmhouses of Rural Japan

RECIPE: Salmorejo

Andalusian Cold Tomato Soup

In Spain, cold soups are perfect for a hot summer’s day. Gazpacho is probably the most well known – a blend of fresh tomatoes and other vegetables, such as cucumber, peppers and garlic. Salmorejo is another cold soup, which also originated in Andalusia. We first tried it in a tapas restaurant when we visit Seville and absolutely loved it. It is a blend of tomatoes but has the addition of bread which thickens the soup. It’s a great soup that also helps to avoid food waste as it works really well if the bread is slightly stale.

In the UK tomatoes aren’t that great. Supermarkets often sell perfectly round, perfectly red tomatoes that basically taste of water. We go to our local market for our toms or grow our own. (And home grown always taste better.) What is great about Salmorejo is that even if the tomatoes are a bit insipid, the flavourings ensure that the dish will be delicious.

Our recipe for salmorejo is really easy to make but you will need a blender. This will serve four if part of a wider tapas meal/starter or two hungry people. Also, it’s the sort of soup that you can make first thing in the morning and let the flavours infuse during the day. It even tastes great after being in the fridge overnight.

Ingredients

About 10 ripe tomatoes

3 slices of stale white bread

Clove of garlic (or another if you like garlic but we prefer subtle garlic here)

Good slosh of extra virgin olive oil

Salt and pepper

1 boiled egg per 2 servings

Couple of slices of ham

Method

First of all the tomatoes need to be skinned. The easiest way to do this is to cut a cross at the end of the tomato (the opposite end to the stalk). It doesn’t need to be precise and it doesn’t matter if you cut into the tomato’s flesh -it’s all going to be blended anyway.

Pour boiling water over the tomatoes and let them sit in the water for a couple of minutes. Then transfer them to a bowl of cold water.

Grab a corner where the slice was made and the skins should just peel away. It’s not the end of the world if you don’t get all the skin off.

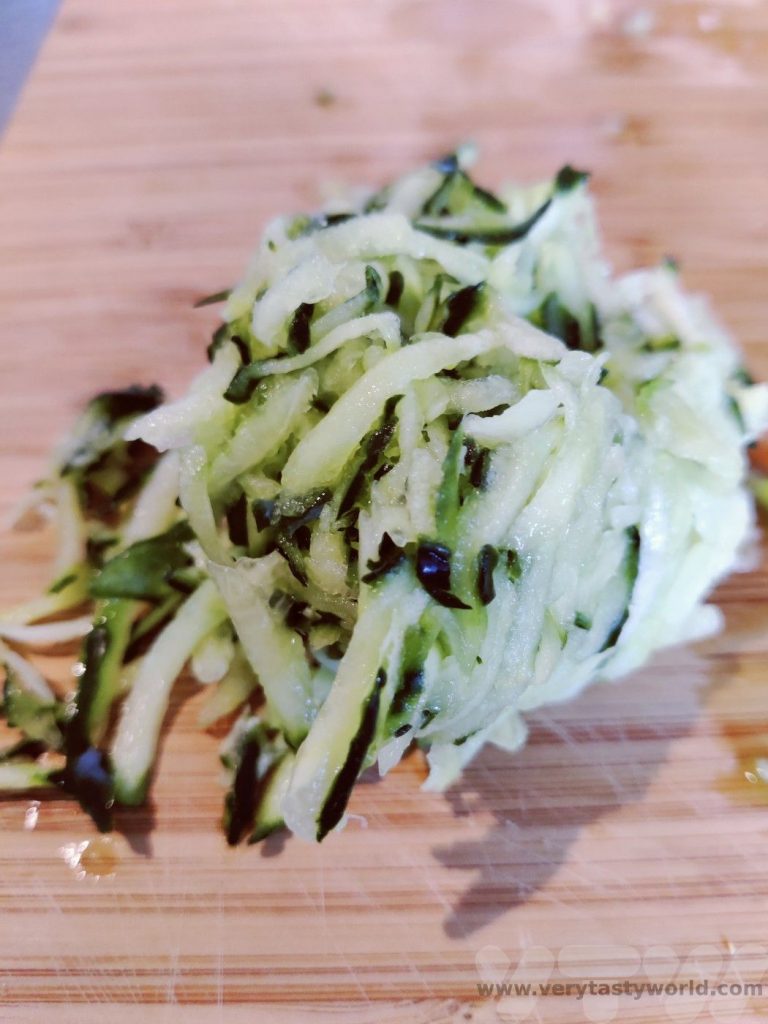

Put the tomatoes in the blender and give them a quick whiz.

Then tear the bread slices and add those, along with the garlic, oil, salt and pepper.

Blend again until you have a smooth, thick soup.

Pour into a jug then put into the fridge and let the flavours infuse.

Serve into individual bowls and garnish with chopped boiled egg and/or chopped ham.

- RECIPE: How To Make Elderflower Champagne

- RECIPE Oyakodon Donburi

- Zero Waste Recipes Before Your Holiday

- RECIPE: Vegetable Biryani Tamil Nadu Style

- RECIPE: Vegan Wild Garlic Pesto

- Recipe: Venetian Pasta Sauce

- RECIPE: Biryani Raita Recipe

- RECIPE: How to Make Costa Rica’s Gallo Pinto

- Recipe: Japanese Simmered Pork Belly – Buta no Kakuni

How Hot Is Wasabi?

A Guide to Fresh Wasabi

Did you know that a lot of the time the fiery, nose-wince-inducing, slightly-eye-watering wasabi that you eat with your sushi doesn’t actually contain much wasabi? The wasabi powders and pastes that you buy in the shops or which are used in many restaurants are usually a combination of mustard, horseradish, green food colouring and just a hint of wasabi, probably from the stem or leaves. Eating fresh wasabi is a completely different experience. And how hot is wasabi?

Growing Fresh Wasabi

Wasabi as a plant is similar to horseradish in that both belong to the Brassica family (which is quite a broad family as it also contains vegetables such as cabbage, broccoli and kale) and both have a fiery pungency but they are different species and offer very different flavours.

Horseradish is really easy to grow in the UK. It’s like a weed and grows rapidly in the wild. We regularly see horseradish growing by the roadside or in parks. (We would like to forage for it but although we could pick the leaves it’s against the law to dig up roots on land you don’t own.) It’s the long white root that provides the flavour. Wasabia Japonica’s flavour comes from its rhizome, which is kind of like a swollen stem.

Traditionally wasabi grows next to crystal clear gravelly mountain streams in rural Japan (a delightfully romantic image) but it is actually possible to grow wasabi in the UK (although our garden is significantly less romantic than a beautiful mountain region). Water grown wasabi is known as sawa- or mizu-wasabi, soil grown is known as hatake-wasabi.

Our soil grown wasabi needs a little love. It likes relatively cool conditions and much prefers the shade to the sunshine. We once had to move our wasabi into a sunny spot temporarily and it wilted like the Wicked Witch of the West. (It recovered 24 hours later when it was back in the shade.) It also needs to be well watered, although it doesn’t like to sit in water. A cool, rainy British summer is ideal. We grow it in pots close to the north facing wall of our house. It takes a while for the rhizome to grow – you need to be patient for a couple of years – but the result is worth it. The cat was very impressed with our attempts.

Eating Fresh Wasabi

The first time we ate fresh wasabi, it was a revelation. It did have that amazing familiar pungency but it also has a sweetness that you don’t expect. One of the advantages of growing wasabi is that the other parts of the plant are all edible: the lovely heart shaped leaves can be used as a garnish (and eaten), the stems chopped up like herbs and even the delicate flowers, which are especially good in a tempura. The other parts are much more mild and, while they impart flavour, don’t have the pungency of the rhizome.

How To Prepare Fresh Wasabi

Wasabi rhizomes can grow up to 100g in size, although some can be bigger. You would have to have a big sushi party to get through that amount but it is possible to store it.

The pungency of the wasabi fades when it is exposed to air, so it is best to grate it just before serving. There are various graters you can buy. Traditionally, a shark skin grater is used, although it is usually made from a type of ray. Purists prefer this, claiming that this is the one that ensures that the wasabi has the best creamy consistency and brings out the best flavour. But you can also get other types, including a metallic grater or, our preference, a ceramic grater.

Using a vegetable peeler, we just scrape off a small amount of the rhizome’s outer layer, up to the length we wish to grate, then grate the wasabi in a circular motion.

One useful little implement is a bamboo brush which you can use to gather up the grated wasabi. The stiff bristles are much more efficient at negotiating the grater’s bumps than our fingers. Gather the grated wasabi up into a nice little ball and serve. It’s worth grating slightly less than you think you will need – you can always grate more.

Storing Wasabi

A fresh rhizome will store well in the fridge for a couple of weeks. We tend to keep it wrapped in damp kitchen paper and grate as much as we need. If we don’t get through an entire rhizome in that time, it tends to go a bit black, so the best thing to do is freeze it. The whole rhizome doesn’t freeze well but grated wasabi freezes brilliantly.

We tend to grate into portions and then store inside little plastic tubs – the sort you get sauces/dips in with a takeaway meal. Then we seal – in order to minimise exposure to the air and pop into the freezer. Take them out when you need them. The portions thaw in no time at all. Alternatively, you can wrap the grated wasabi into parcels of clingfilm.

So How Hot Is Wasabi?

Unlike chillies, which have the Scoville scale to measure their heat level, wasabi heat doesn’t really have a similar measurement system. The Scoville scale is based on dilution of the chemical capsaicin – how much water it takes before you can no longer detect the heat of the chilli. But wasabi is a root not a pepper and instead of releasing capsaicin, it contains allyl isothiocyanate, a compound which is also found in mustard, radish and horseradish. Its pungency is a result of its volatility – the gas it releases feels as though it goes straight up your nose rather than remaining on your tongue like the capsaicin of chilli.

People’s reactions to wasabi will differ quite widely. Some people can scoff the hottest of chillies but can’t take the heat of wasabi. But it is undoubtedly hot! Fresh wasabi has a milder pungency than the horseradish/mustard/green paste.

How To Eat Wasabi With Sushi

Wasabi and sushi go together like fish & chips, salt & pepper and gin & tonic. Wasabi was originally used with sushi in the Edo period in Japan and was thought not only to help mask any smells from the fish it was also considered to have properties that help prevent the growth of bacteria.

The best way to eat wasabi with sushi is to mix it with a small amount of soy sauce in a little dish. Never dip the rice part into the dish – the rice will soak up the soy sauce and all you’ll get is a mouthful of nose-wincing salt, losing the delicate flavour of the fish. Instead, turn the sushi upside down and dip the fish side into the sauce. (It’s absolutely fine to eat sushi with your fingers.) If you are having an omakase meal, where the chef prepares the sushi for you, it is likely that they will add exactly the correct amount of sauce and wasabi, so you won’t need to worry.

We love making chirashizushi – a bowl of seasoned rice with a layer of seafood atop – which we serve with our own fresh wasabi and garnished with the lovely heart-shaped wasabi leaves.

Related Posts You May Enjoy

- Kobe Beef in Kobe – Is It Worth It?

- World’s Best Breakfasts -Breakfast of Champions!

- Recipe: Simmered Shiitake Mushrooms

- How to Use Public Transport in Japan

- RECIPE Oyakodon Donburi

- Planning a Trip to Japan

- The Makanai: Cooking for the Maiko House

- Setsubun Food – Bean Throwing Day

- The Gassho Farmhouses of Rural Japan

- RECIPE: How To Make Elderflower Champagne

- RECIPE Oyakodon Donburi

- Zero Waste Recipes Before Your Holiday

- RECIPE: Vegetable Biryani Tamil Nadu Style

- RECIPE: Vegan Wild Garlic Pesto

- Recipe: Venetian Pasta Sauce

- RECIPE: Biryani Raita Recipe

- RECIPE: How to Make Costa Rica’s Gallo Pinto

- Recipe: Japanese Simmered Pork Belly – Buta no Kakuni

RECIPE: How To Make Kimchi

Kimchi is a fundamental part of society in Korea. It is Korea’s national dish and is usually eaten with most meals there. In fact, kimchi making has been assigned as a UNESCO cultural heritage and even has its own day – 22nd November. Kimchi is great fun to make and we have a recipe for how to make kimchi. It isn’t a traditional Korean style but it’s easy to make, is ready very quickly and we reckon it’s much more delicious than shop-bought.

We first tried kimchi over 20 years ago and it was love at first bite – sour, spicy and crunchy, it has a unique flavour. Being a fermented food it is also purported to have properties that are beneficial for your gut health but, far more importantly, it’s delicious.

It’s surprisingly easy to make but it does take a while to ferment and you do have to watch out for potential explosions but that is what makes it so exciting! (Don’t worry, we’ve been making it for years and have never had an explosion) We have tried fermenting lots different foods over the years, including miso, and it’s a very satisfactory process.

Kimchi is made via a lacto fermentation process whereby good bacteria, known as lactic acid bacteria, convert the sugars in vegetables into lactic acid. The joy of fermentation is that it isn’t a precise art. You need a bit of patience while the bacteria do their thing but once fermentation is complete, the finished product will last for many months, if not years – that is, if you don’t eat it straight away!

Ingredients For Making Kimchi

1 Chinese leaf cabbage (also known as Napa cabbage)

1 carrot

2 spring onions (green onions)

A carrot’s length of daikon white radish, also known as mooli (optional)

2 fat cloves of garlic (3 if your garlic isn’t portly enough)

1 tbs fish sauce (vegetarians can use soy sauce, but use less – 1/2 tbs)

1 thumb-sized piece of ginger

1 tbs Korean chilli red pepper powder known as Gochugaru (you should be able to find this in Asian stores and even supermarkets these days). A variation is to use Korean chilli paste, known as Gochujang. Gochujang is traditional but we prefer the chilli powder for this kimchi.

3 tbs salt. You want to use a salt that doesn’t have anti-caking additives. Table salt isn’t recommended. Equally you don’t really want to use really posh salt. We tend to use Himalayan pink salt.

How To Make Kimchi: Method

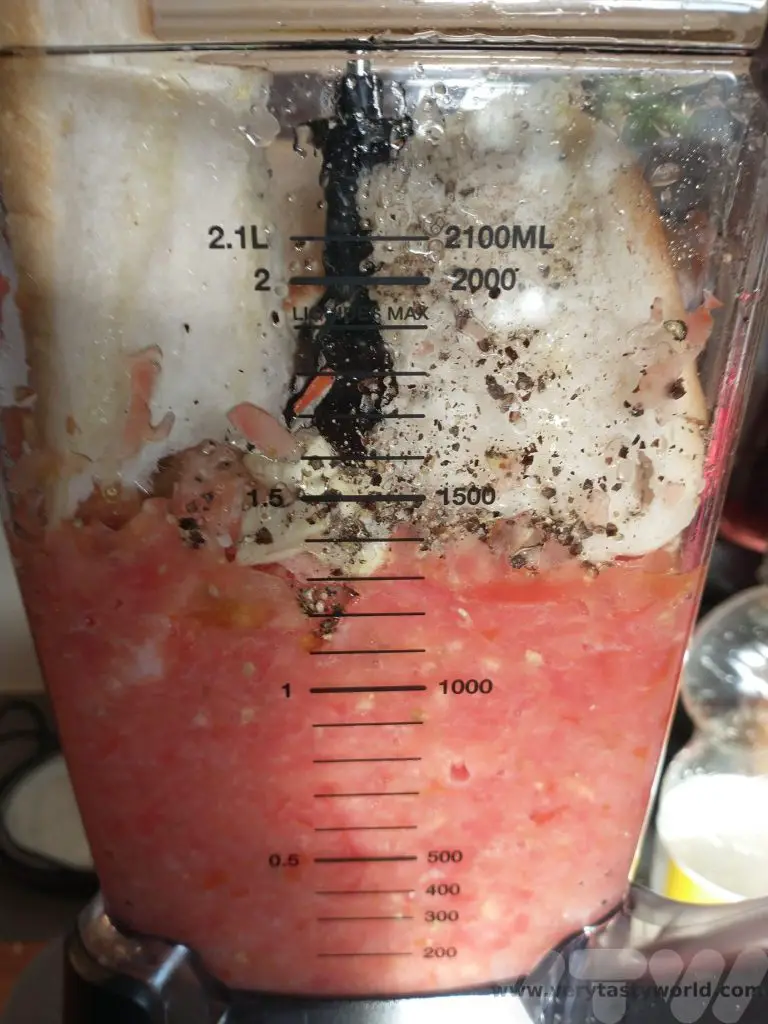

Slice the cabbage into chunks. You want to have easily pick-upable bite-sized pieces. One of the nice things about the Chinese leaf is that it has a lovely broad ribs which retain their crunch when the kimchi is finished which makes a nice contrast with the softer leaves.

Place cabbage into a bowl and sprinkle with the salt. Massage the salt into the cabbage and wait a couple of hours. It is a lot of salt but you will be washing it through later.

Prepare your fermentation jar. The size of the jar is important. You want to fill the jar up as much as possible and not have too much headspace. The jar size that suited our cabbage was 1.4 litre capacity. We recommend clip top Kilner jars as they have a good seal to keep air out but also let the liquid escape. There are some types of jar specifically designed for fermentation. We’ve had greater success with some than others.

The jar needs to be clean. We find the best way to clean the jar is to wash it in warm, soapy water and rinse. Then we boil a kettle and fill the jar (not forgetting the lid) with boiling water. After 10 minutes, drain and let the jar cool down. Some people put the jar into the oven on a low heat for 20 minutes but we haven’t found this step to be necessary for this type of fermentation.

After some time has passed, give the cabbage a quick rinse with water. Have a taste – it should taste salty but not overpoweringly salty. You don’t need to pat the cabbage dry.

Julienne the carrot and daikon, if you are using it, slice the spring onions lengthways.

Put the garlic, ginger and fish sauce into a pestle and mortar and grind them together to create a paste. It will have quite a liquid consistency.

Add the vegetables to the cabbage.

Pour over the garlic-ginger-fish sauce paste and sprinkle the chilli powder over the cabbage and veg. Mix well. We find it’s easiest to do this with our bare (clean) hands.

Then you need to pack the jar. Pick up handfuls of the cabbage mix and place into the jar, pushing down to squish it in – really pressing hard to make sure there aren’t any air gaps.

You should try and aim for minimum headroom at the top of the jar to reduce the air space. You also want to make sure the cabbage mixture remains pressed down. You can get all sorts of weights but a glass dessert ramekin type container (e.g. Gu) works well or, cheaper and less calorific than eating a chocolate dessert, fill a small plastic bag with water, tie at the end and squish into the top of the jar.

Close the jar and place the jar on a deep plate or in a bowl to catch any liquid escaping.

Check The Ferment Over Several Days

Over the next few days the cabbage will begin to ferment. The time it takes will depend on how warm the ambient temperature is. You’ll see a liquid start to form in the jar and cover the cabbage and the lactic acid bacteria will start to form lactic acid and C02. It is because of the C02 that you need to keep an eye on your ferment. If you are using a specific fermentation jar you should be fine. If you are using a conventional jar you will need to ‘burp’ your ferment, at least once a day. Open the lid – very briefly – and close immediately, just to let the C02 out. This will ensure that the pressure doesn’t build up. If you don’t burp there is a risk of the jar exploding. We’ve never had a glass jar break but there have been numerous occasions when I’ve burped the jar and ended up with a brine shower!

The kimchi should be ready within a week to 10 days. You can leave it longer if you wish and this will ensure further development of the flavours.

When the kimchi is ready you can store the jar in the fridge or decant it into smaller jars (just go through the process of cleaning them, then adding boiling water and letting them dry). The kimchi will store in the fridge for months as long as it is airtight.

Beware

The two greatest issues with fermenting food is risk of explosion (which can be reduced/eliminated if you use the right equipment) and mould. When the ferment is exposed to air there is the potential for mould to develop. If you open your jar and see fuzzy mould of any colour you should discard the ferment. It’s heart-breaking but the safest thing to do as the mould could make you very ill. (It’s not advisable to scrape off the mouldy bits – by the time the fuzz has appeared the spores will have permeated the whole jar.) Obviously this creates something of a dilemma – you need to open the jar to burp but don’t want to let the air in. So, the key is to open the jar very quickly to release pressure then close immediately. With some types of fermentation jar you don’t need to worry.

Some Notes On Fermentation Equipment

You don’t need too much specialist equipment to ferment food. A kilner jar with a metal clip lid ‘self-burps’ – it allows CO2 to escape whilst not letting air (which can contain mould spores) in. You can get various fermentation vessels in varying sizes.

Salt should not have anti-caking properties.

You can get chilli flakes or gochujang in Asian supermarkets.

- RECIPE: How To Make Elderflower Champagne

- RECIPE Oyakodon Donburi

- Zero Waste Recipes Before Your Holiday

- RECIPE: Vegetable Biryani Tamil Nadu Style

- RECIPE: Vegan Wild Garlic Pesto

- Recipe: Venetian Pasta Sauce

- RECIPE: Biryani Raita Recipe

- RECIPE: How to Make Costa Rica’s Gallo Pinto

- Recipe: Japanese Simmered Pork Belly – Buta no Kakuni

Please note that this post contains affiliate links. If you click the link and decide to make a purchase we will earn a small commission, at no cost to you, which helps towards running this site.

Places To Visit In Chitwan, Nepal

Cooking Tharu Chitwan Nepal

The Chitwan area of Nepal is a national park that is located around 100km from Kathmandu. It takes around two to four hours to travel there from the capital (sometimes much longer if the roads are busy – our return journey took 10 hours!) depending on the route. But it’s a pleasantly scenic drive across the Nepalese countryside (we travelled there after spending a night at the Neydo monastery) once you have escaped the busy roads of the capital city. It is possible to fly from Kathmandu but this is a more expensive mode of transport. There are lots of places to visit in Chitwan. The area is best known for its wildlife but it is also possible to meet the local Tharu people and learn to cook with them.

Wildlife Walking Safari in Chitwan National Park

Chitwan is best known as a wildlife reserve where you can undertake a boat or walking safari and – if you are amazingly lucky – you may be able to see wild elephants, rhino, bears or even a tiger. If you’re merely lucky you will catch a glimpse of monkeys, deer and birds. And maybe chance upon some rhino poo to prove that they really were somewhere in the forest, honest.

We caught a jeep from our hotel to the river early in the morning and climbed aboard a long boat, so we could float serenely downriver.

There were lots of birds to see, including brightly coloured kingfishers, and we passed by a crocodile, who was almost as long as our boat, also enjoying a leisurely time in the river.

After around an hour we disembarked and met our guide for a walking safari.

We were given a pep talk whereby we learned what to do if we were to encounter any of the amazing, but potentially dangerous, creatures. Basically, they can all outrun you, so:

Rhinos – Stand still if you are downwind from them, they have appalling eyesight and probably won’t see you. Back away. If they charge, run away in a zig zag pattern, climb a tree if you can.

Bears – Do not run, avoid eye contact, back away slowly.

Tigers – Stand your ground. Don’t run, all cats love a chase.

Elephants – If they’re in a strop, you’re doomed!

Sadly, we weren’t amazingly lucky and didn’t get to try any of these techniques as the wildlife had decided not to come out to play, but that’s okay, that’s why it’s called wildlife.We did see a strutting peacock, a monkey and some deer.

But whether you see spectacular creatures or not, walking through the forest or floating along the river makes for a very pleasant morning.

And did meet one tiger!

Places to Visit in Chitwan – A Tharu Village

A less well-known excursion is one which takes you to a nearby Tharu village. Local people welcome you and are happy to introduce you to their traditional way of life. This trip can be arranged via your hotel who will organise transport to the village, which is located just a few kilometres from the national park. All the villagers are very welcoming and are happy for you to wander round. Some of the local women have recently set up a home stay so that you can experience the local way of life first hand. If we were to return to Chitwan we would absolutely love to stay with them.

Cooking With the Tharu People

Even if you’re not staying overnight, you can spend a very pleasant afternoon learning to cook traditional dishes with them. We met our lovely hosts who made sure we had a hands-on approach to cooking, right from the start.

The first element of the meal to start cooking is the rice. First of all, get water. There is no running water in the houses so you have to go to the local pump. Wash the rice then add water to the urn. Next, start the fire. The Tharu use an outdoor clay oven fuelled with wood. The oven is located between the houses.

Some kindling starts the fire and then the wood burns slowly to create an intense but steady heat. Pop the rice into the water vessel, put it on the fire and let it start cooking.

We then went for a walk in the local area to find ingredients. The Tharu grow a lot of their own vegetables on land adjacent to the village. These include onions, rice, beans, wheat and corn. It was particularly interesting to see lentils growing – we’d only ever seen them dried and they only ever came in packets from the supermarket.

Then we started preparing the vegetarian dish that accompanied the rice which was boiling away merrily on the fire. Beans were sliced using a knife by steadying the handle with a foot and – carefully – slicing the beans using the inside of the blade. Other vegetables were added.

We then went onto flavouring and this was something of a revelation. At home we’re very accustomed to using gadgets to process our food. There’s nothing wrong with that – with busy lives, a food processor can save a few seconds with all sorts of routine kitchen preparation jobs. But, actually, crushing garlic with a stone on a rock took no time at all and produced a smoother paste than any garlic crusher we’ve come across.

We removed the rice, which remained piping hot inside its pot and cooked the main dish over the fire. We started by quickly frying off the garlic and then added the vegetables and a bit of water to simmer.

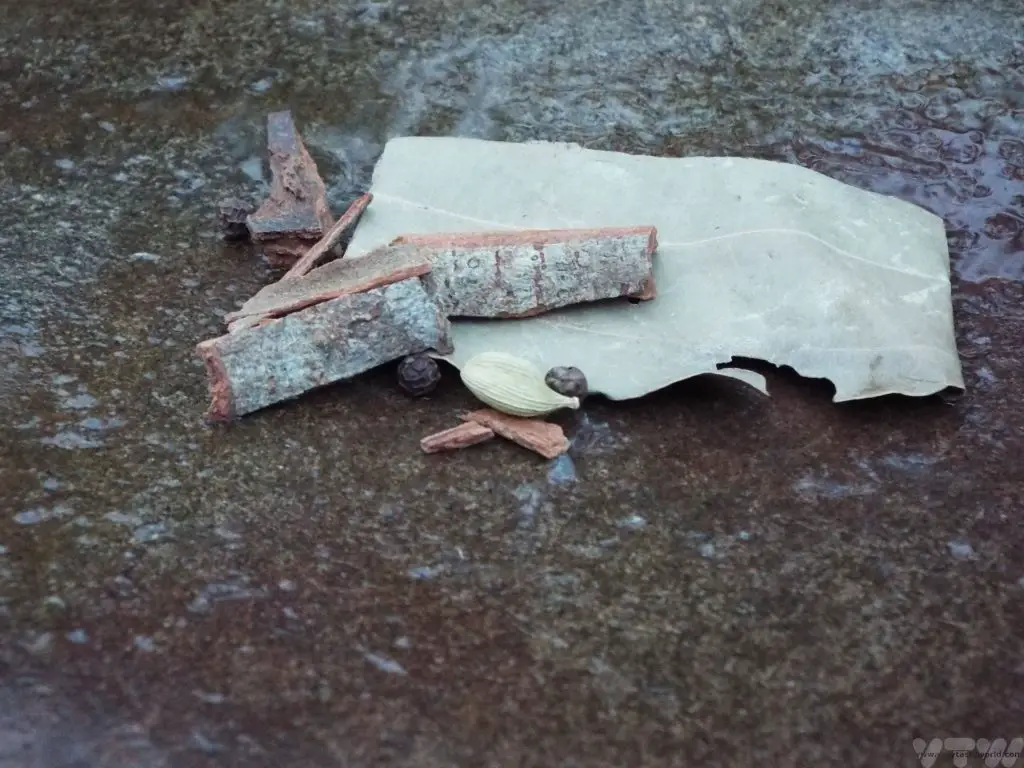

The other thing is that we are also very used to buying powdered spice mixes. Pick up a packet of garam masala, sprinkle into your cooking and… instant flavouring. But so many of us buy spice mixes that are often never fully used before their ‘best before’ dates and languish in a cupboard slowing turning into tasteless dust. And it really isn’t that much more effort grind whole spices. Again, we used a stone. In this instance some dalchini (cinnamon bark), a few peppercorns, a dried cinnamon leaf and a cardamon pod were quickly ground into a masala. And doing it this way also gave us the freedom to change the spice combination. We added this to the dish at the last moment to provide a very aromatic flavour. Which, of course, was delicious.

We shared it with our host family in their home.

The trip also included an opportunity for Mitch to dress up and dance with the local ladies. Photos of her wearing traditional dress and – shock, horror – make-up do exist, but we’ll spare you those. What was great about the trip was not only getting the opportunity to cook and taste delicious local food but also to meet so many lovely people. Our hosts were absolutely charming and the whole village was delighted to see us.

The afternoon with the Tharu was delightful but it also changed the way we think about using spices. After our visit we decided that we would buy whole spices and then we could develop our own flavourings. Much as we’d like to have a grinding stone and a rock it’s not very practical in a suburban English house, but we do use a good quality granite pestle and mortar. It gives us the opportunity to experiment with spice combinations as well as textures – sometime we want a fine grind, other times we prefer a coarser texture. The whole spices can be stored more easily and keep for a longer period of time – especially if using an airtight container.

Related Posts You May Enjoy

RECIPE: How to Make Vietnamese Spring Rolls

How to make Vietnamese Spring Rolls Summer Rolls

Vietnamese cuisine is amongst the most delicious in the world. It is also amongst the prettiest. We have a Vietnamese spring roll recipe. While most people think of spring rolls as being deep-fried, gỏi cuốn are actually served cold – at room temperature. In Western countries they are referred to as spring rolls, salad rolls or even summer rolls. They have slightly different names depending on the region of Vietnam: they are gỏi cuốn, meaning salad rolls in the south and nem cuốn in the north. Apparently they are called “rice paper” rolls in the central regions of the country, which is a simple description but accurate.

Gỏi cuốn comprise cold vermicelli noodles, salad, protein such as prawns or pork and herbs all wrapped up in rice paper, known as bánh tráng. They are usually served with a dipping sauce. Unlike fried spring rolls, these are really fresh and, like so much of Vietnamese food, full of flavour.

Vietnamese Spring Roll Recipe

- Makes 12 rolls

Ingredients

For the Rolls

Rice paper wrappers (you can get these from Asian supermarkets)

100g vermicelli rice noodles

36 king prawns (3 per roll, or one more each if you are feeling greedy), cooked and peeled.

2 carrots

Shredded lettuce or cabbage

Handful of fresh mint and/or coriander (or a herb of your choice)

For the Dipping Sauce

2 tbs sweet chilli sauce

Juice of ½ a lime

Splash of fish sauce (or soy sauce for vegetarians)

How To Make Vietnamese Spring Rolls Method

Prepare the noodles. Pour boiling water over the vermicelli and leave for 5-7 minutes until they are soft. Drain and allow to cool.

Prepare the filling. Shred the lettuce/cabbage.

Finely slice the carrot. There is a tool that you can buy easily in South East Asia which is a little like a vegetable peeler that juliennes the carrot. If you don’t have one of those you could use a mandolin. And if you don’t have a mandolin a grater will do just fine.

The packaging on the paper skins – and many other recipes – states that you only have to soak them in warm water for a couple of seconds. We found that actually some of them need quite a bit longer soaking time. (And some just didn’t go soft at all- those should be discarded, these are not crunchy rolls and will not only not taste very nice, they will have a horrid texture and be really difficult to roll.)

When the paper is super-soft and totally translucent take it from the water and lay it flat on a clean surface. The skins are much more robust than they appear.

Start placing your filling onto the paper. You want to place it around 1/3 to 1/2 of the way up from the bottom of the paper and leave about 2 cm space on each side. Because the papers are partially transparent you can take your time to make the rolls look pretty. To do this make sure that the colourful items such as the prawns, herbs (try to keep the leaves whole for extra prettiness) or carrot are on the bottom of the pile, so that they can be seen through the wrapper.

Add a small handful of vermicelli, remembering that less is more – you don’t want to overstuff the rolls.

Variation: We also added some slices of home-made pickled garlic to some of the rolls to add an extra zingy flavour.

Now the tricky bit: the rolling of the rolls. It’s not as difficult as it might appear. Firstly, pull the filling together and fold the bottom of the paper over it, pressing gently into the filling so that the wrapping is tight.

Next, fold each side in towards the centre of the wrapper to form a little parcel.

Then roll forwards to complete the spring roll, trying to keep the filling inside as tight as possible. The paper is soft so will stick at the end easily. When the rolling is completed, keep the seam on the underside which will also help it stick.

There are a variety of dipping sauces. A popular one is hoisin and crushed peanuts but we made a sweet chilli dipping sauce.

We used sweet chilli sauce, half a lime and a splash of fish sauce to give us that characteristic sweet, sour, salt and spice flavour. Just mix the ingredients together in a bowl. Then it was simply a case of serving the rolls, dipping and enjoying.

How to make Vietnamese spring rolls summer rolls

These are some of the tools and ingredients we used to make the summer rolls:

Please note that this post contains affiliate links. If you click the link and decide to make a purchase we will earn a small commission, at no cost to you, which helps towards running this site.

- World’s Best Breakfasts -Breakfast of Champions!

- A One Day Hanoi Itinerary

- Mekong Meanderings

- A Chiang Rai Temple and A Country Retreat

- A Chiang Mai Tour in Northern Thailand

- Sunrise at Angkor Wat & Other Temples To Explore

- RECIPE: How To Make Elderflower Champagne

- RECIPE Oyakodon Donburi

- Zero Waste Recipes Before Your Holiday

- RECIPE: Vegetable Biryani Tamil Nadu Style

- RECIPE: Vegan Wild Garlic Pesto

- Recipe: Venetian Pasta Sauce

- RECIPE: Biryani Raita Recipe

- RECIPE: How to Make Costa Rica’s Gallo Pinto

- Recipe: Japanese Simmered Pork Belly – Buta no Kakuni